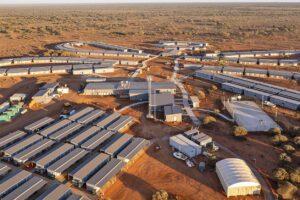

Mine workers and FIFO camps go hand in hand. But turning to drugs and alcohol to cope with the isolation that comes with fly-in fly-out work. The Mental Illness Fellowship of Queensland CEO Tony Stevenson writes about the up(per)s and down(er)s of FIFO life.

Spotting whether a workmate is physically up to the task in the workplace can be a straightforward matter. Spotting whether a workmate is grappling with their mental health? Not so much.

Having a mind gripped by irregular thought patterns, diminished concentration, stress, anxiety and depression, is still widely seen as an intensely private matter, and some people work hard to mask their very real pain. For many workers, alcohol and drugs are used as a coping mechanism.

RELATED CONTENT

- A short history of Australian Mining

- New FIFO Mental health code launched

- Mineworkers ride for Mental Health Awareness

- Workplace Culture and PsychoSocial Risks on Regulatory Agenda

Thanks to a lack of evidence-based data, there are varying views on just how prevalent mental health issues and the extent of substance use are in the mining industry. In turn, that makes it difficult for companies to come up with workable strategies.

It is, however, recognised that there are mitigating factors, such as living in remote communities, a lack of support networks, and heavy workloads.

Some research projects have been making inroads over recent years. One is research from Lifeline WA and Edith Cowan University psychologists. They conducted an anonymous online survey of 924 Fly-In-Fly-Out (FIFO) and Drive-In-Drive-Out (DIDO) workers. The results showed a higher prevalence of psychological distress amongst workers in comparison with the general population.

Another piece of research, Mental Health and the NSW Minerals Industry, was prepared for the NSW Minerals Council by the University of Newcastle and the Hunter Institute of Mental Health.

They estimated that in any 12-month period between 8,000 and 10,000 workers in the NSW mining industry experience a mental illness. More particularly:

- An estimated 5,777 employees in the NSW Minerals industry are likely to have experienced anxiety disorder in a twelve month period;

- Approximately 2,500 would have experienced depression; and

- An estimated 2,000 experienced a substance use disorder.

According to Drug Arm Australasia, the mining sector is not unique when it comes to alcohol and other drug use, with:

- Annual costs of alcohol absenteeism alone valued at $1.2 billion.

- Annual costs for alcohol and other drug use (not including tobacco) amounting to approximately $5.2 billion in workplace injuries and deaths and lost productivity.

- Alcohol use contributing to 25 per cent of workplace accidents and five per cent of all Australian workplace deaths.

- Across all industries, it is shown that males are more likely than females to drink at risky levels.

- Male workers are also more likely to use illicit drugs.

Combine a mental health issue with substance use and you have what we refer to in the mental health sector as Dual Diagnosis, or co-morbidity.

Once again data is limited, but an estimated 30 to 40 per cent of people experiencing mental illnesses and about half of people living with severe mental illnesses also experience issues related to substance use.

In addition, men are more likely to develop a co-occurring disorder than women.

Because there are many combinations of disorders that can occur, the symptoms of dual diagnosis vary widely. The signs that alcohol or drug use may be problematic include:

- Withdrawal from friends and family

- Sudden changes in behavior

- Needing to spend more money to get the desired effect

- Using substances under dangerous conditions

- Engaging in risky behaviors when intoxicated or under the influence of alcohol or drugs

- Loss of control over use of substances

- Doing things you wouldn’t normally do to maintain your use

- Developing tolerance and withdrawal symptoms

- Feeling like you need the substance to be able to function

The symptoms of a mental health condition also can vary greatly. Someone displaying warning signs including extreme mood changes, confused thinking or difficulty concentrating, avoiding friends and social situations could be in need of help.

Mining is one of the most heavily tested industries for drug and alcohol use in Australia – safety issues alone demand that.

The industry records a higher than average rate of short-term risky drinking with:

- 9 per cent drinking high levels of alcohol at least monthly.

- Around 12 per cent of the mining industry workforce engaging in illicit drug use.

The higher incidence of alcohol and other drug use can be linked to be linked to FIFO lifestyle factors including:

- Employees are mostly male;

- Work environments are isolated with lack of infrastructure and entertainment;

- Boredom;

- Long, irregular hours;

- Easy access; and

- Living in manufactured communities that lack the psychosocial supports of true communities such as schools, neighborhoods, families, sports group, etc.

Consequently the point of connection in these communities is based around alcohol and illicit drug use.

Anecdotal trends indicate that workers are also using drugs that they know will be “out of their system” by the time they are tested on site. It is also recognised that this can lead to workers experimenting with new and emerging drugs, particularly legal drugs that can be purchased online, that aren’t currently tested for.

To make meaningful change, organisations need to dig deeper – look for the underlying causes. Awareness, education and support systems are critical, which is why some companies have established committees to help develop and implement substance-free workplace policy.

Such a committee needs to involve employees, occupational health professionals, management and unions where applicable. Input from community specialists is also invaluable.

It’s important that any formal policy:

- Clarifies expectations as well as the consequences of non-compliance;

- Provides clear statements about what the purpose of the policy is and what the desired outcomes are;

- States who is covered: full and part-time staff, students, interns, third parties, volunteers and independent contractors;

- States how the policy will apply to work-related social events, off-site events or other non-routine business events;

- States how the policy complies with privacy and confidentiality legislation;

- Outlines a clear process for notifying a manager if there is a concern about a co-worker’s fitness for duty due to issues related to substance use;

- Describes any conditions under which drug or alcohol testing may be required;

- Describes potential disciplinary actions; and

- Provides details of employee assistance programs.

That last one is important, because support and understanding can often go much further in solving a problem than punitive measures.

Education for employees should include:

- Workshops that aim to dispel the stigmas and stereotypes associated with substance use (aligning those messages with the stigmas attached to mental illness);

- Information about the effect of substance use on workplace safety, health and performance, professional and personal relationships;

- Information on spotting potential signs of substance use;

- Clear communication about your substance-free policy, including key messages about objectives and responsibilities;

- Provide information on topics like smoking, alcohol and other drug use, gambling, and other problematic behaviours, as well as links to community resources;

- Seek out professional speakers who can talk about their own experiences; and

- Find out what your employees enjoy doing in their down time, and encourage healthy behavior through activities that suit: organized walks or fun runs, sporting events and alcohol-free social gatherings.

Managers also need to consider potential safety concerns, and risks to the health of the employee, productivity, performance, reputation, morale and quality of work or service.

Consider workplace situations when behaviours related to substance use might be difficult to detect, be potentially hazardous or are more likely to occur due to higher levels of stress, accountability or responsibility.

All of these steps require a considerable commitment from organisations. But given that many people experiencing substance use or mental illness issues don’t seek help, it’s important to recognise the role that education and early intervention can play.

The bottom line is employers do need to take more responsibility and contribute to the overall health and wellbeing of their employees – after all a happy, healthy worker is a productive worker.

This article was written in collaboration with Drug Arm Australasia.

If you, a friend or work colleague have a question about mental illness, or are looking for support in your local area (including drug and alcohol services), contact Mi Networks by phoning 1800 985 944 from anywhere in Australia, or visiting www.minetworks.org.au. Mi Networks can connect you to the services that you are looking for.

Read more Mining Safety News

Add Comment