[hr]No one could have imagined that in the small but prosperous town of Creswick in 1882 there would occur the worst gold mining accident in Australia – a record that stands to this day. [hr]

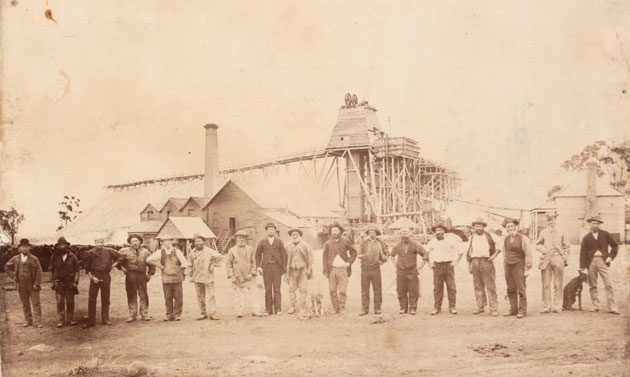

The evening of 11 December 1882 was no different from any other when 41 night shift workers reported for shift at the New Australasia Mine No. 2 approximately 2km from Creswick. The men descended 250 feet down the mine shaft then made their way another 2,000 feet to the face and started mining.

The evening of 11 December 1882 was no different from any other when 41 night shift workers reported for shift at the New Australasia Mine No. 2 approximately 2km from Creswick. The men descended 250 feet down the mine shaft then made their way another 2,000 feet to the face and started mining.

Unknown to anyone working at the mine, a dam of water had been steadily building in the disused Australasia No. 1 mine, not far from the face they were working. Some time around 4.45am on the morning of 12 December, without warning, the wall of the reef drive burst from the pressure of the water, flooding the Australasia No. 2 mine and engulfing the workers.

Like the 2006 mine accident at Beaconsfield in Tasmania, relatives, friends and onlookers would wait at the mine-head anxious for news. Whilst rescue in Creswick would occur within three days (unlike the fortnight it took to rescue the miners at Beaconsfield), 22 men would not return to their family. The disaster would leave 18 women widows and 63 children orphans.

The noise of the flooding was heard above ground and immediately the engine driver, James Spargo, began to increase the speed of the pump. He was soon joined by the other two engine drivers – James Harris and Thomas Clough.

The Mine Manager, William Nicholas, who was asleep when the accident happened, was soon on the scene. By 9.30am the news was circulating Creswick and people started to congregate at the mine. By midday, word was circulating from Creswick to other towns and villages and would soon spread throughout the Colony of Victoria.

The trapped miners had managed to reach the very small space of the No.11 jump-up. There they huddled together in darkness, singing hymns and praying for deliverance and for their loved-ones. Some wrote messages on their crib pails to their families. The Bellingham brothers tied themselves together for fear they would be separated.

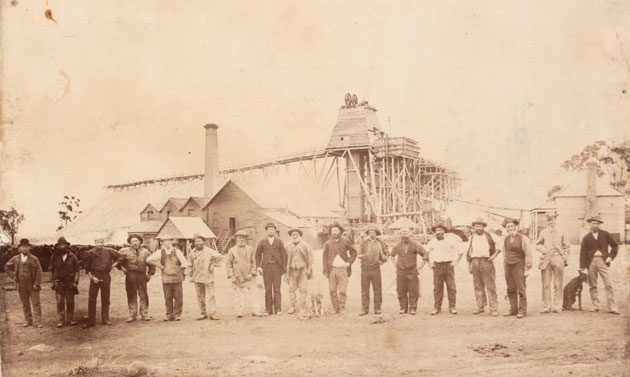

For almost three days the three engine drivers from the mine ran the engines at over 10 times their normal speed, in an attempt to lower the water and save the trapped men. A special train was sent from Melbourne with specialist diving equipment. This equipment was borrowed from the H.M.S. Cerbrus along with competent divers.

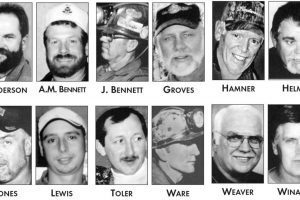

When the rescue came Thursday morning unfortunately it was too late for 22 men (one body was still warm) and only 5 men came out alive from the foul smelling mine shaft.

The funerals of the men took place the next afternoon. Every mine in the district was shut so all could attend the funeral – in fact the whole town shut up shop so everyone had the chance to say their last goodbyes. Shortly before his untimely death one of the trapped miners, John Tom Clifton, forecast that their funeral would be the biggest ever held in Creswick. He was proved right. About 4,000 people marched in the procession, including 2,000 members of the Miners’ Association, with 15,000 onlookers.

[pullQuote]“Unknown to anyone working at the mine, a dam of water had been steadily building in the disused Australasia No. 1 mine, not far from the face they were working.”

[/pullQuote]Nineteen of the miners are buried in Creswick Cemetery.

Similar to the Black Saturday Bushfire Fund, an appeal was started for the widows and orphans of the victims. Money was collected from towns and villages all over Victoria and soon amounted to £20,000. The widows received 15 shillings per week and the orphans from 5 to 1 shilling until they started employment or reached 17 years.

Within two years Parliament had changed the fund to “The Mining Accident Relief Fund Act, 1884” for the benefit of all victims of mining accidents. The Fund was finally wound up in 1949 long after the last widow had died. A memorial was erected in the cemetery to commemorate the tragedy.

[hr]The Inquest

Following is an extract from The Argus newspaper, 13 January 1883.

“…The most important evidence taken was that of Mr. A. T. Walker, Government mining surveyor, who showed that No. 2 shaft was 55ft nearer the old workings than was indicated on the working plans of the mining manager, and therefore Mr. Nicholas’s calculations of the distance he had to drive to intersect the old drive was incorrect.

In reply to this Mr. Nicholas stated that as the new drive was at least 20ft below the old one, with a reef between them, he was quite justified in extending the drive, but it transpired that even the difference in the levels was unavoidably only the result of an estimate which would require certain conditions in the ground to bear out.

The real distance between the two workings has not yet been discovered, owing to the ground having become dangerous since the water came in. Again, the new workings were defended on the ground that culverts had been put in to drain the old workings, and that the stream running through them was large enough to prevent any accumulation of water in the original reef drives. It was admitted that the danger signal —knocking on the air-pipes—was faulty, because in repairing the pipes they often had to be hammered ; but according to Mr. Nicholas, a wire and bell would be inconvenient to maintain, and flood-gates might drown more than they would save.

It came out clearly enough that no danger of flooding had been apprehended either by the manager or any of the miners who were examined, although a softness and “fretting” had been observed in the face for a couple of days prior to the inburst taking place…”

[hr]Resources

Creswick Museum – www.creswickmuseum.org.au

Creswick a Living History – www.creswick.net/buildings_and_places/australasia_mine

Add Comment