In 1994, the lives of eleven men were lost in the Moura No. 2 mine disaster after an explosion ripped through the underground coal mine in Queensland. AMSJ spoke exclusively to district chief safety inspector Greg Dalliston, a man who received a haunting phone call on the night of August 7, a man who comforted the families of those lost, and a man who says those miners should have never made that final, fateful descent underground.

Twenty-one men were working underground at the Moura No 2 mine, located east of Moura in Central Queensland, on August 7, 1994.

At 11.35pm, an explosion tore through the mine and only ten men escaped. The remaining men, working in a more southern area, failed to resurface.

Two days later, on August 9, a second, more violent, explosion shook the mine at 12.20pm. It was after this devastating blast that all rescue efforts were abandoned and the mine sealed, with all workers assumed dead.

The entombed miners included a crew of eight undertaking first workings for pillar development, as well as a beltman, a sealing contractor and an assisting miner.

It was the last deadly explosion in the Moura mining district, but it certainly wasn’t the first. The mining town was no stranger to tragedy, with two other explosions shaking the community.

Ultimately, there was failure to withdraw persons from the mine while the potential existed for an explosion.

On September 20, 1975, thirteen miners died at Kianga Mine after an explosion, which was found to have been caused by spontaneous combustion. The mine was sealed and the bodies of the thirteen men were never recovered.

Eleven years later on July 16, 1986, 12 miners were killed at Moura No 4 Mine after an explosion. The blast was thought to have been initiated by either frictional ignition or a flame safety lamp. In this case, the bodies were recovered.

The Moura No 2 explosion brought the total number of lives lost in Moura to 36. A number too big for any close-knit community, let alone one with a population of only about 1500; a number that has shattered the heart of Moura, and a number that has left a town in mourning for their loved ones who perished.

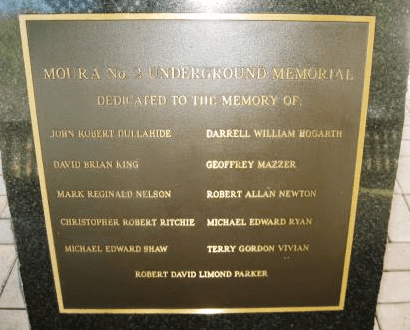

A memorial sits in the middle of an open, grassy area at the Moura No 2 mine. A tombstone stands in the centre of a fenced area littered with crosses, photos and flowers, the names of eleven men listed on the glossy stone.

The bodies of these men are buried deep below this patch of country, the truth of what happened on that day buried with them.

A midnight call

District Chief Inspector Greg Dalliston received a phone call around midnight on August 7 with the chilling news that something terrible had happened at the mine.

His despair soon turned to anger, when he recalls the information he learnt when he arrived at the Moura No 2 mine in the early hours of August 8.

“I got the call that Sunday night… I still remember that,” Greg says.

“From there we turned up at the mine to find out that we haven’t even been told the real story.”

Greg says the company knew they had sealed up Panel 512 due to heating that weekend, and knew the risks of an explosion when they sent the men to work that night.

“Some of those people actually knew when it was going to go into explosion range, yet they let those blokes go underground. So, I was pretty angry.

“Talking to the blokes afterwards and they knew there was a haze coming out, like it was getting that hot, like you see on the edge of the hot roads out in Central Queensland in summer, so you knew it was a heat haze.

“Those people knew what was happening, if we knew all that now, what we found out 18 months after the Inquiry sat, then I think we should have been asking for some prosecutions because they knew what they were doing and sent people down there, and they got killed.”

Greg recalls speaking to the families of the lost miners, who shared his anger.

“The families were pretty upset, as you can imagine,” he says.

“First it was their loss, but then after that, it was anger. So after we finished the investigation… we decided we needed to get out of town. We couldn’t stay in town, we couldn’t go down the pub, we couldn’t go and talk to families because they were finding out more and more and they were getting angrier and they didn’t have bodies to see, to bury, they were entombed in the mine which was one of the decisions I had to make.

“You live with that for the rest of your life and it’s pretty hard to say ‘we’re going to push dirt over before we have another explosion’.”

Greg returned to Moura at the end of the week for the memorial service, where the community had been filled with rage, with media reports highlighting more and more information about what actually happened in the days leading up to the explosion which claimed the lives of their loved ones.

“That was pretty hard, going back, and that’s when the families starting attacking some of us, saying ‘Why didn’t you do anything? Why didn’t you stop people going underground?’,” Greg says.

“We didn’t even get told.”

Moura No. 2 mine disaster – Mining Wardens Inquiry

Greg sat in on each of the 65 tireless days of the Inquiry, headed by Frank Windridge, which started in October 1994 and was handed down on January 17, 1996.

The Inquiry found that the first explosion originated in the 512 Panel of the mine and resulted from a failure to recognise, and effectively treat, a heating of coal in that panel. This, in turn, ignited methane gas which had accumulated within the panel after it was sealed.

The cause of the second explosion remains unknown.

“On the basis of the available evidence the Inquiry has concluded that sealing of the 512 Panel after completion of production, resulted in the buildup of methane to explosive concentrations within the panel,” the Inquiry says.

… we couldn’t go and talk to families because they were finding out more and more and they were getting angrier and they didn’t have bodies to see, to bury, they were entombed in the mine which was one of the decisions I had to make.

Greg Dalliston, 2016.

“Evidence before the Inquiry also strongly indicated that a heating arising from spontaneous combustion of coal was present in the panel for some time prior to sealing. The heating was of sufficient intensity to act as a source of ignition for gas in the panel, and this combination was the immediate cause of the first explosion.”

The Inquiry said contributing causes to the first explosion were identified as a “number of failures in responses, approaches or systems at the mine”.

These included a failure to prevent the development of a heating within the 512 Panel; a failure to acknowledge the presence of that heating; a failure to effectively communicate and capture and evaluate numerous tell-tale signs over an extended period; and a failure to treat the heating or to identify the potential impact of sealing with the panel consequently passing into an explosive range due to the methane gas accumulating in the panel.

“Ultimately, there was failure to withdraw persons from the mine while the potential existed for an explosion,” the Inquiry says.

The final descent

There were three key questions facing the Moura mine management on the night of Sunday, August 7 1994, prior to the explosion, according to the Warden’s Inquiry:

Should the men go underground? What do we tell them? What if they raise concerns?

That afternoon, mine deputy Mr Blyton became aware of the general trend in the atmosphere of the 512 Panel and in particular, that the area was indicated to enter the explosive range sometime between 11.30pm and midnight.

He observed the Maihak system a number of times during the shift and noted the progression toward the explosive range on the Ellicott diagram which the system displayed.

In a telephone call to Mr Mason on the Sunday evening at around 6.30pm, Mr Squires relayed the gas trend information and canvassed how the night shift crew should be approached.

“It was estimated that by the start of the night shift the CO concentration would be of the order of 130 to 140ppm and that indications were that sometime during the night shift the atmosphere in the 512 Panel would enter the explosive range (greater than 5 percent methane),” the Inquiry says.

“Opinion was that the 512 Panel was behaving much as expected.” The men sent underground on that ill-fated day were expected to hear of the possible heating signs in the mine through the “grapevine”.

Undermanager-in-charge George Mason said he did not believe miners going underground on that fateful night needed to be informed of a tar smell or haze that had occurred just days before, because there was “quite a good grapevine at work”.

“I know that the communication channels especially on that shift are very good and information flows freely amongst all the people. That’s the opinion I formed,” he said.

But survivors of the tragic events on August 7 confirmed this was not the case.

“If I thought there was any danger in going down there, I wouldn’t have gone down,” survivor Jimmy Parsons said.

Miner Greg Young’s described the scene underground during the blast that killed his workmates.

“I saw Jimmy Parsons and my younger brother Darren thrown into the air,” he said.

“My ears popped pretty painfully. The pressure felt like my head was exploding.” Another survivor, Peter Ein, was diagnosed with carbon monoxide poisoning after the blast. He was one of three survivors who told the Inquiry that management had not warned them of potential dangers in the mine.

He said undermanager Michael Squires had spoken to the men twice before they went underground, but had not used those conversations as an opportunity to mention problems regarding rising gas levels, smells or haze.

“We should have been told,” Mr Young said.

Mr Squires was told by his superior George Mason to not mention the issue unless miners raised concerns.

“George said not to raise it with anyone on the shift because they would… if they had a concern, they would raise it with me,” he said.

The Inquiry said Mr Mason’s reply, in essence, was that if no one else raised a concern then neither should Squires and that if anyone elected to not go down the mine then they should not be forced to do so.

Mine deputy Neil Tuffs told Mr Mason on the day before the explosion, that he would not be sending his drilling team down when it went through the explosive range. He did not go to work on Sunday afternoon because he did not think men would have gone underground.

“I really thought we were advancing as far as safety went in the mine,” he told the Inquiry.

“If a question is raised such as this, where it’s a life and death situation… I would have expected a positive answer.” Mr Windridge said in his Inquiry that “events at Moura surrounding assumptions as to the state of knowledge of the night shift… and the safety of those at the mine, represent a passage of management neglect and nondecision which must never be repeated in the coal mining industry”.

“Mineworkers place their trust in management and have the right to expect management to take responsible decisions in respect to their safety. They also have the right to expect management to keep them informed on any matter likely to affect their safety and welfare.

“It is regrettable that the air of caution, arising out of uncertainty, which was exhibited at the mine in order to bring forward the sealing of 512 Panel did not extend to the general safety and welfare of the workforce and, in particular, to informing and keeping persons out of the mine for a time subsequent to that sealing.”

Fatal miscommunication – Moura No.2 mine

In total there were a significant number of reports of ‘smells’ from the 512 Panel during its life, some as early as June, and these proved to be fleeting.

Undermanager Mark McCamley told the Inquiry he smelt a “very slight tarry smell” in the 512 Panel on June 17, seven weeks before the deadly explosion.

He said he was concerned about the smell as it could have indicated early signs of heating, but did not record the smell in his shift report.

Instead, he said he told the manager in charge of the mine Albert Shaus, and senior undermanager George Mason.

“He did not say that to me,” Mr Mason said at the Inquiry later, calling Mr McCamley a “liar”.

On the first day of the Inquiry deputy mine manager Michael Caddell told how he detected a strong tar smell in the mine which was “similar” to an odour he smelt after the 19861986 explosion in Moura No 4.

He had expressed concerns two days before the explosion, telling his superior he had smelt a tar smell while taking gas readings and that the mine needed to be sealed immediately.

Mr Caddell said he told undermanager Michael Squires of his concerns, leading to the early sealing.

He said a policy had been in force at the No 4 mine where workers left the mine after sealings while gas passed through the explosive range. He said a similar policy was not adopted at the No 2 mine.

Mine deputy Cole Klease, also said he recalled a ruling after the fatal 1986 explosion that after sealing, there would be a 48-hour period where no men would be allowed down the pit. But he said this was not practice at Moura No 2.

Mr Klease, also a member of the Mines Rescue team, said he entered the mine on August 6, the day before the explosion, after an employee had commented on the atmospheric conditions.

Upon inspection, he noticed a “benzeney, tarry smell” and possible haze.

Shift undermanager Michael Squires told the Inquiry he did not recall several warnings of possible heating in the mine. He said he did not recall a phone conversation with Mr Caddell, on the Friday before the explosion, telling him he recorded 10 parts per million carbon monoxide at cross-cut 10 and a strong tar smell. He also said he didn’t recall an earlier phone call in June from another deputy who reported a tarry smell.

Mr Squires was challenged with being “far less than truthful” in his evidence to the Inquiry, in regards to not being able to recall mine deputies telling him of possible heating smells in the mine, claiming he was not aware of the significance of certain gas calculations to determine if a sealed panel was heating, and saying he was unaware of high gas levels registering and alarming on a computer he was required to monitor.

He also testified while he knew the gas levels were increasing, he had not been concerned because he didn’t properly understand what they meant.

It was an “industry fact” underground coal miners were not trained in spontaneous combustion, state Mines Rescue service deputy chief David Kerr told the Inquiry.

He said he wasn’t surprised so many mine deputies had no training in spontaneous combustion.

In an unfortunate twist of fate, the mine’s ventilation officer was on holidays at the time of the explosion. Allan Morieson told the Inquiry dangerous carbon monoxide levels and heating could be seen clearly from the data collected in the days before the explosion.

However, a graph plotting the rise of carbon monoxide in the mine on the eve of the explosion was drawn incorrectly and did not show the true steep increase. The same graph was later believed to have been plotted after the blast, but Mr Morieson said it was “not wrongly calculated or miscalculated or a bungled graph”.

It was also heard the 400m-long 512 Panel had only one gas monitor, placed 20m in from the seals.

Mine safety legislation “Written in blood”

“When the Inquiry recommendations got handed down, to go back and tell the families that nothing was going to happen to anyone that didn’t make the right decisions was pretty tough,” Mr Dalliston says.

“But all you could do is go back and say we at least have this report and the five other reports, at least the legislation now is something those people have got to hang onto.” This year will mark 30 years since the Moura No 4 explosion, which killed 12 workers in July, 1986.

“There’s been over 50 people killed in that town… It’s a nice town to go to, the people are great, but what the poor buggers have been through, you can see in their faces, every time there’s an anniversary. It doesn’t matter which one their family was lost in or involved in, they all feel the same, they all feel the loss,” Greg says.

“But those people left us this mining legislation. Those families will never get over what they have been through, nor will some of us… But the main thing is, if we ever lose some of the stuff we had in place because they lost their lives – I think we would have to go and stick it right in the government and the companies.

“It’s made in blood, it’s written in blood.”

The Warden’s inquiry into the Moura No.2 mine disaster made the following recommendations

Spontaneous Combustion Management

It is recommended that all mines be required to develop and implement a spontaneous combustion management plan along the lines outlined to provide effective long term control of that risk and which satisfies any requirements of the Chief Inspector of Coal Mines as a condition for the continued operation of the mine.

Mine Safety Management Plans

It is recommended that mines be required to put in place Mine Safety Management Plans to cater for key risk areas. It is further recommended that Mine Safety Management Plans be based on detailed risk/hazard analyses.

Training and Communications

It is recommended that all employees be effectively trained to recognise indicators of specific mine hazards, such as spontaneous combustion, and their control; and become sufficiently familiar with mine gases, and associated risks. All persons holding statutory appointments must undertake training in communications, and completion of a retraining course each year.

Statutory Certificates

It is recommended that the procedures for granting statutory certificates for underground coal mining and the conditions under which they are awarded, be reviewed.

Statutory certificates for underground coal mining are not to be granted for life, but for intervals of not less than three and not more than five years.

Ventilation Officer

It is recommended that a position of ventilation officer be established as a statutory position at all underground coal mines.

Self Rescue Breathing Apparatus

It is recommended that a representative industry working party to be convened by the Chief Inspector of Coal Mines and that group be charged with the development of guidelines for the industry covering life support for escape.

Emergency Escape Facilities

It is recommended that a working party be set up, comprising persons with appropriate knowledge and experience, to examine and report on a range of issues relating to emergency escape facilities.

Gas Monitoring System Protocols

It is recommended that mines be required to develop and implement protocols for the setting, resetting, and the noting and acceptance of alarm conditions raised by any gas monitoring system in use at the mine.

Sealing – Designs & Procedures

The Inquiry recommends that the location of final seals are subject to approval by the District Inspector of Mines; it be a requirement that seals be constructed using only materials that have been approved and the Chief Inspector of Coal Mines should determine and then apply requirements appropriate for the design and installation of seals and for their long term stability.

Mineworkers place their trust in management and have the right to expect management to take responsible decisions in respect to their safety.

The Inquiry recommends that the minimum requirements provide for: the continuous and effective sampling and monitoring of the atmosphere in a sealed area; means whereby the pressure difference between the inside and outside surfaces of seals can be measured; the effective ventilation of the outside surfaces of seals; and regular inspection and periodic auditing on the long term performance of seals and sealed areas.

No part of a mine is to be sealed without the prior written approval of the District Inspector of Mines.

Withdrawal of Persons

It is recommended that mines be required to develop and implement protocols, as a statutory requirement, for the withdrawal of persons when conditions warrant such action. It is further recommended that the Chief Inspector of Coal Mines convene an appropriate industry working party to develop guidelines for the use, in turn, of mines in the development of protocols for the withdrawal of persons.

Inertisation

It is recommended that the research which has been previously undertaken by the committee which was instigated as a result of the Moura 1986 Inquiry be evaluated as soon as possible in order to determine the most appropriate method of inertisation for Queensland coal mines.

It is further recommended that funds be made available through the government in order to obtain such a system, such that equipment for the inertisation of a coal mine or parts of a mine, with appropriately trained people and operating systems, be readily available for use.

Research into Spontaneous Combustion

It is recommended that funds be made to undertake an exhaustive international literature and data search, to critically review the literature and data and to prepare a comprehensive state-of-the-art report on the subject of spontaneous combustion in coal mines.

Panel Design

It is recommended that it be made a requirement of Part 60 (Second Working Extraction) submissions that spontaneous combustion be specifically included as a factor to be considered and evaluated.

Mine Surface Facilities

The Inquiry recommends that underground mines develop a surface area plan showing the location of mine entries, ventilation fan, access roads, surface installations, administration buildings and other infrastructure. It is further recommended that both new and existing mines make provision for the rapid sealing of the mine from the surface through the installation of an air lock facility in at least one of the mine intakes for ready access to re-enter the mine.

Literature and Other Training Support

It is recommended that spontaneous combustion handbooks be revised and updated and a supply of the handbooks be maintained with provision of periodical review of content for updating. Appropriate audiovisual aids to be produced for education and training purposes,and coal mines to establish a reserved area accommodating a basic library of safety literature and other learning materials available for mine officials and mineworkers to consult at any time.

All courses of instruction for certificates of competency in coal mining be required to include adequate instruction on spontaneous combustion using appropriate supporting literature, case study material and other learning aids.

Future Inquiries

The Inquiry recommends that the Act be amended to enable either proxy or alternative members to fill temporary or permanent positions on the panel or for an Inquiry to continue with a reduced number of panel members.

Have we learned from our lessons?

“I don’t believe that we have learnt enough,” Greg says, even though the Moura No 2 explosion was the last explosion to rock the Queensland or New South Wales mining industries.

“We had Box Flat in 1972, but after that from 1975 to 1994, in twenty years, we had four major explosions in Queensland and New South Wales, all of those were at BHP-owned mines, which ended up killing a total of 50 people,” Greg says.

“It’s disappointing that in the last five to six years, BHP is probably one of the worst companies for maintaining lessons from the past.

“The government has been lucky to attract some inspectors because of the downturn in the industry over the last four years, and that has helped a little bit with an increase in the quality of the inspectorate and some of those inspectors are trying to make a difference.

“The problem is that most of the newer managers coming through now don’t even know about the Moura report and what the recommendations were, they hear someone wants a new legislation, but most of them haven’t actually been back and had a look at the Moura report from 1994, let alone the Kianga, Appin, Box Flat or Moura No 4 report.” Greg says one of his biggest concerns is that not all of the recommendations made by the Inquiry have been put into place.

“Everyone puts their hand on their heart and says that all the recommendations from Moura report have been put into place,” he says.

“We know that we’ve have three goes at putting in something to say no tickets for life – three to five years for tickets – we’ve had three committees over 20 years try to put those in place… They should be in place sometime early this year. But they are not in place yet.

“The Queensland Resources Council are saying that we don’t need as many statutory tickets, which was one of the main things to come out of Moura – having people who were trained and regularly retrained. The Board of Examiners recommended and supports an increase in the number of statutory certificates, something we wait and see what the current state government does but from the regulatory impact statement that was put out, we believe that that will happen.” “Spontaneous combustion and ventilation training at underground coal mines, which is a recommendation of Moura, has turned to the stage where, except for a couple of mines that are having a go, it’s nearly not existent.

“If you’re a contractor, you only get trained on what you need to do, and you don’t need to know your environment, so if we do have a disaster again, then those people will always struggle to know what to do to get out of a mine without some assistance.” He says a recommendation for SIMTARS to develop training, audio-visual aids and training standards still hasn’t happened, and neither has a recommendation for Australia to produce and distribute technical and scientific manuals.

“Another issue that has come up in underground mines and open cut mines is the training communications recommendation, so training for those deputies and people that write statutory reports and do statutory inspections,” he says.

“We’ve had a number of fatalities occur in mines in Queensland over the last two years and some of the contributing factors at least of those has been that those reports, inspections and communications haven’t been done to a right standard.

“So, again, we are seeing a downturn and the edge falling off some of our controls we have in place. Have we learnt lessons from the past? “I think the safety operations management systems we have in place have definitely stopped explosions. The safety operations management systems are there to protect the workers, but in some cases, it might have been by the grace of God, otherwise pure arse.

“So I don’t think we’ve learnt from the past, and I think there is a lot of people out there that don’t understand the past and unfortunately they’re disappearing every day, the people that do understand it, they are getting older and the new people through think ‘it won’t happen to me’, and that’s why we had explosions in 1972, 1975, 1979, 1986, 1994.

“I hope that we have another ten years at least of no more explosions. Because I don’t want to have to go and talk to another family and tell them why their father, mother, brother, sister, isn’t coming home.”

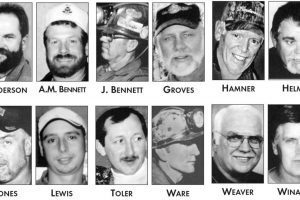

John Robert Dullahide, 44, Beltman

Darrell William Hogarth, 46, Miner

David Brian King, 24, Miner

Geoffrey Mazzer, 45, Electrician

Mark Reginald Nelson, 36, Miner

Robert Allan Newton, 39, Deputy

Robert Parker, 39, Contractor

Christopher Robert Ritchie, 27, Miner

Michael Edward Ryan, 31, Miner

Michael Edward Shaw, 27, Miner

Terry Gordon Vivian, 49, Miner

The inquiry in the Moura No. 2 mine disaster found that the first explosion originated in a sealed mine panel (a block section of the mine) and resulted from a failure to recognise, and effectively treat, a heating of coal in that panel. The heating coal ignited methane gas which had accumulated within the panel after it was sealed. The inquiry did not reach a finding regarding the cause of the second explosion.

REFERENCES

Queensland Warden’s Court, Wardens Inquiry: Report on an Accident at Moura No 2 Underground Mine on Sunday, 7 August 1994, 1996, CAC0152. Read the full report here

Read more Mining Safety News

Add Comment