One of the most remarkable rescues and survival stories in Australian history involved 160 miners, a great train dash, underwater divers and Herbert Hoover, who was to become president of the United States, writes Tony Stephens.

The central character was Modesto ‘Charlie’ Varischetti, a 32-year-old widower and father of five, who was carried to safety after nine days underground at the Westralia mine at Bonnievale, 12 kilometres from Coolgardie.

A thunderstorm hit the West Australian goldfields on 19 March 1907, trapping 160 men underground. All but one scrambled to safety; Varischetti was presumed drowned because of the volume of water that flooded the main shaft.

Varischetti, from Gorno, in Lombardy, had lost his wife, Maria, while she gave birth to their fifth child. The Catholic Church suggested he go to Australia, where mining work was plentiful, and he could send home his earnings.

After miners and mine management gave their workmate up for dead, those on the surface heard tapping in miner’s code from below. They realised he was alive, probably trapped in an air pocket.

A high-capacity steam pump was rushed to the mine but the water level had been lowered only a few centimetres by nightfall.

The local mining inspector, Josiah Crabb, reported that clearing the shaft would take up to a week, and there was no hope of rescue. Newspapers around the world dubbed Varischetti “the entombed man”. They published daily bulletins of Varischetti’s pitiful signalling from below.

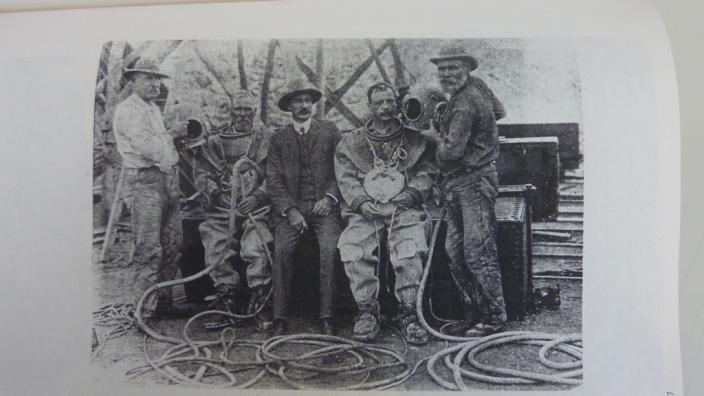

A chance remark by Crabb’s seven-year-old son, John, triggered the dramatic rescue attempt. “Why don’t you use a diver, Dad?” the boy asked. Crabb sent for two divers in Kalgoorlie, Frank Hughes and Thomas Hearn; he also sent for Herbert Hoover. Michael Throssell, a retired journalist who is writing a film script about the rescue, says that Hoover, then the manager of the Sons of Gwalia mine at Kanowna, was the highest qualified mining engineer on the goldfields.

The nearest air hose long enough to reach Varischetti was in Fremantle, 560 kilometres away. The West Australian government ordered a special train, the ‘Rescue Special’, which cut nearly two hours off the 12 hour run to Coolgardie, setting a world record for the distance. At Coolgardie, fast horses rushed the equipment to Bonnievale.

READ RELATED

- To The Rescue | A case study of the training practices of the Mine Rescue Team at Golden Grove, Western Australia.

Hughes made his first exploratory dive on the fourth day of Varischetti’s ordeal. He and Hearn made three separate descents on day five, and on day six, when they first reached the trapped man, Hughes took a powerful electric lamp, food, candles and sealed letters of encouragement from Giovanni Varischetti, Modesto’s brother, who was on the surface.

The pumping was working, but the rescue plan became more desperate as Hughes told Crabb on day eight that Varischetti would not survive much longer.

On day nine, the divers gave the miner more food, shared cigarettes with him, tied a rope around his waist and started the arduous walk through waist-deep water and knee-deep sludge. At one stage, Varischetti’s mouth and nose only just cleared the water. He staggered to the surface on March 28, after 206 hours underground. He recovered to return to work underground but died of fibrosis at 57.

“…the rescue plan became more desperate as Hughes told Crabb on day eight that Varischetti would not survive much longer.”

The following article was published in the Sunday Times (Perth, WA), Sunday 24 March 1907.

HUGHES THE HERO

A “Sunday Times” representative this evening buttonholed Diver Hughes, who said:-

‘’Prior to going to work on the South Kalgurli Mine, where I am employed as a miner, I heard that a diver was required at the Westralia mine at Bonnievale, and with the desire of doing what I could to save a life I told the manager that I was prepared to offer my services. I went below at the South Kalgurli about 1.30 ‘ o’clock, but shortly afterwards was called and told that my offer had been accepted. I then left for Coolgardie by the half-past two train. On arrival I made a careful study of the plan of the Westralia mine submitted to me by Inspector Crabbe.

“As a result of my inspection I felt certain that I could get down the pass from No. 9 level and reach the man. A special train bringing two other divers and gear arrived from Perth at about 4am. I reached the mine at 6.30 and we went below at 8.30am and I made the first descent at 10.30 from the No.9 to the No.10 level. I cleaned out the chute and waited for the arrival of an assistant, but there was no appearance of him. I went up again.

“I went down again shortly afterwards, but assistance did not come to light. Arrangements were then made for another diver (Hearne) to come down. Then somehow or other a misunderstanding took place while we were underwater. However, this being subsequently satisfactorily adjusted, I made my way along the drive to the rise at about 12 o’clock, leaving the other diver at the bottom of the rise so that he could attend to the lines.

“I followed the air pipe line through the level for a distance of about 250 feet, and on going up the rise found the air line and shook it four times. At the fourth shake I received an answering signal from Varischetti. Being thus assured that the man was alive and well, I made my way back to the No. 9 plat for a requisite spell. At about 4 o’clock I made another descent, taking a quantity of food in concentrated form and hermetically sealed, an accumulator, electric light, candles and matches.

“I may mention here that I heard the man sing out before he could possibly have seen me. I passed up the food and light, and in addition slate, which for protection had a wooden covering. Varischetti did not appear to understand the slate business at all, so I removed the covering and passed it to him again. When it came down I took it along to the plat but owing to the action of the water, the message he wrote was quite undecipherable. The slate bore the following message from the manager of the mine, Mr Rubischaum:- “Courage; rescue you in a few hours; food and light for you; keep above timber.”

Read more Mining Safety History

We need to get the Italian made documentary “My name is Charlie” to show in Australia, it is a very good account of this remarkable event .

Made in Australia and Gorno Italy