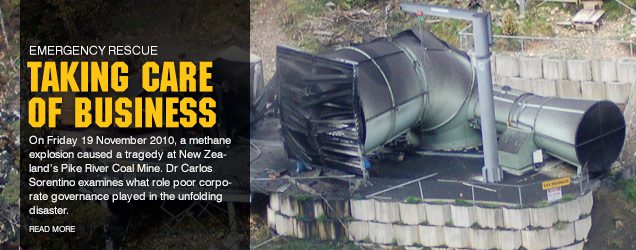

On Friday 19 November 2010, a methane explosion caused a tragedy at New Zealand’s Pike River Coal Mine resulting in the deaths of 29 workers. Dr Carlos Sorentino examines what role poor corporate governance played in the unfolding disaster.

This article outlines the details of the incident and summarises the findings of the Royal Commission which reviewed the accident. It offers some reflections on the issues associated with corporate governance and on the ethical responsibilities of such a venture in the hope that these reflections may help to improve the governance of corporations.

The Pike River Coal mine tragedy

The Pike River Coal Mine tragedy was caused by a methane explosion that happened in the afternoon of Friday 19 November 2010 when 31 miners and contractors were working at the mine. Two men in the stone drift, some distance from the mine workings, managed to escape.

The remaining 29 workers were believed to be at least 1,500 metres from the mine’s entrance and, according to the final report of the Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy, they;

“Died immediately, or shortly afterwards, from the blast or from the toxic atmosphere.” []

“The immediate cause of the first explosion was the ignition of a substantial volume of methane gas… methane gas, which is found naturally in coal, is explosive when it comprises 5 to 15% in volume of air. In that range it is easily ignited. Methane control is therefore a crucial requirement in all underground coal mines. Control is maintained by effective ventilation, draining methane from the coal seam before mining if necessary, and by constant monitoring of the mine’s atmosphere.” []

There were three other explosions over the next nine days; the second on 24 November, a third explosion occurred on 26 November, and a fourth explosion occurred on 28 November 2010.

“The board and the management were under considerable pressure to bring the mine to the desired production levels.”

The Pike River Coal Mine tragedy ranks as New Zealand’s worst mining disaster since 1914 when 43 men died at Ralph’s Mine in Huntly. In the Commission’s words:

“The 29 men who died follow a long line of other people who have perished in New Zealand mines over the previous 130 years. This, sadly, is the 12th commission of inquiry into coal mining disasters in New Zealand. This suggests that as a country, we fail to learn from the past.” []

READ RELATED STORIES ON PIKE RIVER

The Company : Pike River Coal Limited

Pike River Coal Limited is a New Zealand company that was admitted to the official list of the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) on 24 July 2007.

The mine began production in early 2008, and was initially expected to produce around one million tonnes of coal per year for around 20 years. At an estimated cost of $174 million, Pike River Coal was supposed to be the largest underground coal mine and the second-largest coal exporter in New Zealand. []

At the time of listing, the Company had a market capitalisation of about NZD400M. Shares were held by New Zealand Oil & Gas (31%) as well as the two Indian companies; Gujarat NRE Coke Limited (10%) and Saurashtra Fuels Private Limited (8.5%). 7.9% was held by minority shareholders and the remaining 42.5% was sold to the public. []

By August 2010, development costs had blown to $288 million. The mine was producing well below expected levels and the Company had posted net operating losses of $13 million in the year to June 2009, and $39 million in 2010. []

In November 2010, the Company Directors were John Dow (Chairman and Independent Director), Stuart Nattrass (Independent Director), and Non-executive Directors Raymond Meyer, Dipak Agarwalla and Arun Jagatramka.

The board and the management were under considerable pressure to bring the mine to the desired production levels. The mine had a number of technical setbacks. By mid 2009, the mine was still not producing at expected levels and the first 60,000 tons coal shipment was delayed until early 2010. According to the Chief Executive Gordon Ward, the delays were caused by technical difficulties with the mining equipment that the Company had installed in the mine. These delays put Pike under considerable financial pressure forcing them to seek relief from their financiers. []

These difficulties led to the dismissal of Gordon Ward who had led Pike from initial conceptual design in 1996 until October 2010. [] Ward was replaced by Peter Whittall who had joined Pike as the General Manager Mines in 2005 and was responsible for on-site construction, mine development and recruitment at the Pike River operation. [] A 29-year veteran miner and mining executive, Whittall worked for about 24 years in Australian underground mining operations in New South Wales for BHP Billiton, the world’s largest mining company. []

After the tragedy, Pike River Coal was insolvent. The company was placed in receivership on 13 December 2010. Two days later, the receivers announced that 114 of 157 staff would be made redundant immediately, with compensation. Other staff and contractors were terminated with no compensation. Nine months later, in September 2011, Peter Whittall was sacked from his position as Pike’s Chief Executive Officer.

At the time Pike was bankrupted, its market value of $400 million plus an investment of about $290 million were wiped out. In addition, the mine’s 17.6 million tonnes of hard coking coal reserves were sterilized thus depriving New Zealand of this resource estimated to have a sale value of $2.3 billion.

The Royal Commission

On 28 November 2010, the NZ government announced a Royal Commission into the mine tragedy, formed by Hon. Justice Graham Panckhurst (Chairperson), Stewart Bell PSM and David Henry CNZM.

The following July, the Commission began hearings. Two years after the disaster, in November 2012, the Commission released its Report, where it outlined a litany of problems and painted an unrelenting picture of failure at virtually every level of the operation.

The mine remains closed to this day and, therefore, the exact cause of the explosions could not be exactly determined:

“It is not possible to be definitive, but potential ignition sources included arcing in the mine electrical system, a diesel engine overheating, contraband taken into the mine, electrical motors in the non-restricted part of the mine and frictional sparking caused by work activities.”

The Commission found Pike River Mines had insufficient ventilation and drainage systems which could not cope with everything the company was trying to do – driving roadways through coal, drilling ahead into the coal seam and extracting coal by hydro mining. There was no one at the mine responsible for ventilation management. During the first explosion the main fan failed. A back-up fan was damaged during the explosion and did not start automatically and the ventilation system shut down.

The commission slammed Pike River’s management for not properly assessing the health and safety risks its workforce was facing. The Report found the mine’s board of Directors ignored health and safety risks and should have closed the mine until they were properly managed:

“It is the commission’s view that even though the company was operating in a known high-hazard industry, the board of directors did not ensure that health and safety was being properly managed and the executive managers did not properly assess the health and safety risks that the workers were facing. In the drive towards coal production the directors and executive managers paid insufficient attention to health and safety and exposed the company’s workers to unacceptable risks. Mining should have stopped until the risks could be properly managed.”

The original exploration of the geology of the area had provided insufficient information. It had been surveyed using a 14-borehole exploration programme. “This led to adverse unexpected ground conditions hindering mine development,” the report found. During the construction of the mine, the bottom section of the ventilation shaft collapsed and a bypass had to be built to reconnect the upper part of the shaft.

When Pike River Coal Ltd began construction of the mine, it was problematic from the outset: “History demonstrates that problems of this kind may be the precursors to a major process safety accident. Whether an accident occurs depends on how the company responds to the challenges and the quality of its health and safety management.”

The Royal Commission Report states that the Directors of the company exposed workers to unacceptable risks in their drive to produce coal. The commission blamed a, “Culture of production before safety,” as the cause of the men’s death. In the report, the Commission asserts:

“The board did not verify that effective systems were in place and that risk management was effective. Nor did it properly hold management to account, but instead assumed that managers would draw the board’s attention to any major operational problems. The board did not provide effective health and safety leadership and protect the workforce from harm. It was distracted by the financial and production pressures that confronted the company.”

The Royal Commission Report cites numerous warnings of a potential catastrophe at the mine:

“There were numerous warnings of a potential catastrophe at Pike River. One source of these was the reports made by the underground deputies and workers. For months they had reported incidents of excess methane (and many other health and safety problems). In the last 48 days before the explosion there were 21 reports of methane levels reaching explosive volumes, and 27 reports of lesser, but potentially dangerous, volumes. The reports of excess methane continued up to the very morning of the tragedy. The warnings were not heeded.”

The Commission concluded that the Board of Directors failed in their governance role over the mine and rejected Board Chair John Dow’s testimony that, “No safety concerns were reported to me.”

Following the report, three former Directors of Pike, John Dow, Ray Meyer and Stuart Nattrass, denied the Commission findings that production was prioritised ahead of safety at the mine. They went on to accuse the Commission of basing its view upon conjecture or impression, and not the evidence: “Its report does not identify any particular circumstances, or any documents, in which a safety requirement was not met for financial reasons or because it might have impacted upon production,” and added the commission had ignored the evidence it received from senior management who emphasised that, while encouraging production, safety was always their highest priority. []

The NZ Department of Labour came in for particularly heavy criticism for failing to properly supervise operations at Pike River. According to the Commission, the mine was new and owner, Pike River Coal Ltd, had not completed the systems and infrastructure necessary to safely produce coal. Despite these serious failures, the Department issued authorizations for the mine to operate before it was ready to do so, thus creating the circumstances of the tragedy.

“The Department of Labour did not have the focus, capacity or strategies to ensure that Pike was meeting its legal responsibilities under health and safety laws. The department assumed that Pike was complying with the law, even though there was ample evidence to the contrary. The department should have prohibited Pike from operating the mine until its health and safety systems were adequate.”

The commission described the Department of Labour’s performance in relation to health and safety in the mining industry as being, “So poor both at the strategic and operational levels, that the department lost industry and worker confidence.”

Following the criticism of the Department of Labour, Ms Kate Wilkinson resigned as the Minister of Labour adducing the mining tragedy happened ‘on her watch’ and she felt that to resign was the right and honourable thing to do. She retained her other portfolios and remains in the NZ Cabinet.

The commission made 16 recommendations, including that the Government set up a new agency to focus solely on health and safety, and recommended the introduction of tougher regulations to govern underground mining.

The Commission also recommended workers be given greater powers and proposed that unions be allowed to appoint check inspectors with the power to close a mine if it is found to be unsafe. Other recommendations included:

- improve the collaboration between regulators to ensure health and safety is considered before permits are issued

- the Crown Minerals regime be changed to ensure that health and safety is an integral part of permit allocation and monitoring

- review the statutory responsibility of company directors for health and safety in the workplace to better reflect their governance responsibilities

- conduct an urgent review of emergency management in underground coalmines

- activities of the Mines Rescue Service need to be supported by law

- require underground coal mines to have modern equipment for emergencies.

Department of Labour’s Prosecution

In November 2010 the Police and the Department of Labour began investigating the causes of the accident for grounds for prosecution. A year later on, the Department concluded what it described as the, “The most complex investigation ever undertaken by the Department,” involving a team of 15 departmental officers and over 200 interviews. []

In November 2011, the Department laid 25 charges under the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 for alleged health and safety failures leading to the accident.

Section 49 and Section 50 defines unsafe workplace offences and made them criminal offences that upon conviction may result in prison sentences under Section 49(3) (a).

The charges were:

Pike River Coal Limited: Four offences of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure the safety of its employees; five offences of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure the safety of its contractors, subcontractors and their employees; and one offence of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure that no action or inaction of its employees harmed another person.

VLI Drilling Pty Limited: One offence of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure the safety of its employees; one offence of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure the safety of contractors, subcontractors and their employees; and one offence of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure that no action or inaction of its employees harmed another person.

Peter William Whittall: Charged, as an officer of Pike River Coal Limited, with four offences of acquiescing or participating in the failures of Pike River Coal Limited as an employer; four offences of acquiescing or participating in the failures of Pike River Coal Limited as a principal; and four offences of failing to take all practicable steps to ensure that no action or inaction of his as an employee harmed another person. []

The receivers for Pike River Coal Limited declined to defend the charges that lay against the company.

On 31 July 2012, the contracting company VLI Drilling, who had lost three employees in the accident, pleaded guilty in the Greymouth District Court. On 26 October 2012, it was fined $46,800. []

Peter Whittall did not appear in court. Nine months later, in July 2012, he was given a warning over his failure to enter a plea over the charges and, on 25 October 2012, he entered not guilty pleas to the twelve charges laid against him. In a previous opportunity, in February 2012 in evidence at the commission, Whittall’s lawyer denied all charges that his client was in any way responsible for the tragedy. The lawyer added the methane could have been ignited by contraband such as cigarette lighters, carried into the mine by the workers. A spokesperson for some families of the dead miners, Bernie Monk, interpreted this as an attempt by Whittall to shift the blame.

Section 54B establishes a statutory limit of six months from the date of the event; therefore, not further prosecutions will be made under this Act.

Business Ethics

In New Zealand, as in most other countries, a corporation is an artificial person, a legal entity made by a number of real persons that came together for the purpose of undertaking some economic activity. The law recognises a company as an independent legal entity, a body corporate. This means companies are treated as being a separate ‘person’ from their directors and shareholders. This, as well as the whole body of commercial law, defines the philosophy of business: commercial companies are formed with the simple purpose of making money and aim to increase the wealth of those participating in the profits of the company.

It must be emphasised that a company is a structure aimed to minimise individuals’ financial risks. In the words of the Government of New Zealand:

company … members are not personally liable for the entity’s debts and liabilities. Shareholders of a limited liability company are not liable for the business debts of the company (subject to any personal guarantees given) – they are only liable (to the liquidator) for any unpaid money owing on their shares. If they have fully paid for their shares prior to the company being placed in liquidation, they will have no further liability to the company’s creditors.[]

In turn, this poses questions about the ethics and social responsibilities of a company. Ethical issues include the rights and duties between a company and its employees, suppliers, customers and neighbours and its fiduciary responsibility to its shareholders.

Ethical considerations mean that a corporation may need to act in a manner that is not to the benefit of its owners. For example, it may be in the social benefit that a company makes expenditures to reduce pollution beyond the amount that is in the best interests of the corporation. In this sense, the doctrine of social responsibility implies the acceptance of the view that political mechanisms, not market mechanisms, are the appropriate way to determine the allocation of scarce resources to alternative uses. And this poses a fundamental conundrum between business ethics and the raison d’être of a company: if the fundamental purpose of a company is to maximize shareholder returns, then sacrificing profits to other concerns is a violation of its fiduciary responsibility.

“Whittall’s lawyer denied all charges that his client was in any way responsible for the tragedy.”

If this line of reasoning is accepted, it then follows that companies cannot have responsibilities outside their primary obligation of maximising the financial returns to shareholders. In the words of the Economics Nobel Prize Milton Freedman,

“A corporation is an artificial person and in this sense may have artificial responsibilities, but “business” as a whole cannot be said to have responsibilities, even in this vague sense. The first step toward clarity in examining the doctrine of the social responsibility of business is to ask precisely what it implies for whom… the only entities who can have responsibilities are individuals … A business cannot have responsibilities. So the question is, do corporate executives, provided they stay within the law, have responsibilities in their business activities other than to make as much money for their stockholders as possible? And my answer to that is, no, they do not.” []

Whatever one thinks of the validity of this reasoning, this pragmatic view is prevalent amongst a large proportion of businessmen and ‘informed public’. A multi-country 2011 survey found support for this opinion, ranging from 30 to 80% [], indicating that regardless of its rhetoric or moral value, the prevalent view amongst decision-makers is that a corporation’s primary obligation is to increase the wealth of its owners.

The Board of Directors of Pike River followed Freedman’s argument that claims of corporate social responsibility are, at best, mere rhetoric: There is neither a separate ethics of business nor is one needed. [] In this sense, they acted in a legal manner and as they were supposed to do when they prioritised production ahead of any other consideration. In this sense, it is disingenuous to argue that safety was their highest priority: in their view, to submerge the economic profit to a secondary position would have been a breach of their fiduciary obligations.

This moral dilemma – profits ahead of social responsibility – was caused by the division between company and individual responsibility. If a company’s primary aim is to make profits, then the ultimate responsibility of not causing harm – primum non nocere – must rest with its directors and managers as individuals.

Individual directors and managers of a corporation have a primary and ultimately personal responsibility to protect the welfare, health and safety of the community, an obligation that should always come before their responsibility to sectional or private interests. In the words of a professional association Code of Ethics …” The interests of the community have priority over the interests of others,” [] an ethical obligation that must take precedence over any other consideration, including legal obligations.

Ethics as the philosophy of morality (from the Latin moralitas “proper behaviour”), differentiates intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are right and those that are wrong. In the simplest of terms, ethical behaviour is dictated by the Golden Rule, “Treat others how you wish to be treated,” [] a moral rule found in tenets of most cultures through the ages, testifying to its universal applicability. This is a categorical imperative which roots morality in humanity’s rational capacity and asserts certain inviolable ethical laws, laws that in their core hold that human beings have absolute, natural rights. It speaks of good will, the desire to do what is right. Bad consequences could arise from an action that was well-motivated. However, there is a categorical moral imperative of good will which occurs when people act ethically because it is that person’s duty, out of respect for others, respect that Kant defines as, “The concept of a worth which thwarts my self-love.” []

Unless ethical obligations are clearly recognised and accepted by the law and the community at large, tragedies like Pike River will repeat as they have so many times in the past.

PROFILE

Dr. Carlos Sorentino

Dr. Carlos Sorentino is an engineering and resources’ economist specialising in the analysis of capital decisions in the mining sector, the economic evaluation of business, the quantitative analysis of risk of existing and new ventures and in complex economic and corporate studies.

Carlos is the Principal of Ekos Research Pty Ltd and President of Ekeko S.A., firms of independent consultants, technical auditors and resource asset valuers to the international mining and quarrying industries.

REFERENCES

Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy. Two volumes. Wellington, New Zealand. ISBN: 978-0-477-10378-7. October 2012. In this paper, this Report is used as the main source of information and is referred to as “RC.”

RC, vol 1, page 12

RC, vol 1, page 3.

Digging deep around New Zealand.” LG – New Zealand Local Government, Volume 44 No 5, Page 18, May 2008.

Read more Mining Safety History

Add Comment