The 24th of July marks the anniversary of the Appin coal mine disaster which saw fourteen miners lose their lives in a gas explosion. Australian Iron and Steel, a subsidiary of BHP, were at the helm.

The night of Tuesday, July 24, 1979, left 38 children fatherless and wives in disbelief that such an incident could ever occur in a modern mechanised coal industry.

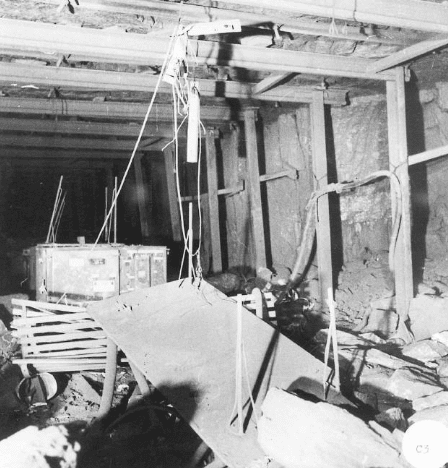

The gas explosion was ignited by a rush of methane gas around 11 pm in a three heading panel approximately 3 km from the surface and at a depth of 600m.

Andrew Hopkins Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the Australian National University in Canberra and former criminologist wrote ‘It was just another working Tuesday for the men at Appin. One shift had ended, a new one begun-and one of the maintenance jobs that needed seeing to during that shift was an auxiliary exhaust fan which helped to suck the methane out of the network of tunnels hundreds of metres underground.

An electrician went down with a supervising “deputy” in charge of operations. The electrician found the trouble and fixed the problem. One last thing to do-test the fan. He threw the switch. The motor sparked. And the methane exploded. The fireball killed 14 men that day-including the electrician and the “deputy”’

Ten of the miners that evening were enjoying a crib break when they were killed. Four were found dead near the working face.

Thirty-one survivors reached the surface, with some sustaining severe burns.

The controversial inquiry into the disaster by His Honour, Judge A. J. Goran Q.C., Court of Coal Mines Regulation concluded in his report that a methane explosion started the coal dust explosion, following an accumulation of methane resulting from a flawed ventilation change.

He concluded that the explosion began by ignition in the fan starter-box and not the deputy’s safety lamp, as initially speculated.

“I do not suspect that the deputy’s lamp contributed in any way to the explosion. Indeed, having studied in detail the investigation of safety lamps, their defects and their inability, despite those defects, in most cases to propagate flame externally, I believe that reports of overseas explosion in mines where safety lamps have been indicted as the cause should be treated with great reservation now.”

“Methane gas in the fan starter-box ignited and propagated to the outside via methane gas nearby, most probably in the vicinity of the exhaust. The flame was conveyed by the vent-tubing to the concentration of methane gas at the closed end of ‘B’ stub, causing rapid deflagration and explosion,” wrote Judge Goran in his report.

Appin coal mine disaster controversy

Appin Coal Mine was always known as a high-risk mine because of the methane concentrations encountered. The circumstances surrounding the disaster brought significant controversy in respect of the worker’s failure to take actions on constantly alarming equipment, the constant strive for production above safety by the company and the actions of the NSW Government mines inspectorate in preventing a disaster that they knew was in the making.

Eight days before the disaster, the mines minister sent a letter to mine saying “the quantities of methane give me cause for considerable concern”

“the quantities of methane give me cause for considerable concern”

NSW Mines MINISTER, 8 days before the appin coal mine disaster

Former deputies spoke of the complacency that existed at the mine prior to the accident. They spoke of the challenges of ‘looking after the safety and keeping up production’

The wife of one of the mineworkers said in an interview “stopping of the job too frequently by deputies caused a deputy to be punished’ She explained that her husband had stopped the face continually on safety reasons and his undermanager saw fit to demote him to work in the back levels.’

Miners interviewed following the disaster said ‘people just went like mad and threw safety precautions to the wind.’ There was rampant defeating of methane alarms at the mine.

When questioned why this was the case the men alluded to production bonus targets. “People have mortgages to look after” they said.

But miners were not the only ones to blame for the Appin coal mine disaster, the Government had written to the mine on previous occasions in an aim to tighten the rules but it went on deaf ears to the mining company who believed their interpretation of the legislation surrounding gas was correct. The department took nine months to respond to Appin coal mine management and failed to update the Department with changes to ventilation plans until after the disaster.

Miners also spoke of problems with the inspectorate visiting the mine and also highlighted that the inspectorate had approved the relocation of gas monitors to prevent alarms triggering.

Do the mines inspectors undertake spot checks? No, I’ve never seen them said, one deputy.

Miner’s said “Most times we know the Government inspectors are coming. We pretty the place up or used to pretty the place up. Stone dusting, the deputy used to run around like a chook with his head cut off getting everything cleaned up and making sure that everything was Ok when the inspector arrived.

They know which district the inspector was coming into. ‘They just made the conditions right for the Government inspector. It happened for years that I know of’ one former deputy said.

In his concluding remarks of his article on the Appin Coal Mine disaster, Hopkins wrote Miners are paid a wage plus a productivity bonus which depends on how much coal is produced.

Safety regulations which slow production or which require the temporary cessation of mining thus work to the miners’ economic disadvantage.

The companies have so structured the situation that miners have a vested interest in ignoring safety regulations when they interfere with production. It is clearly up to governments to legislate against this situation.

A worker’s safety should not be at the expense of his income. Indeed, workers should be entitled to refuse to work in situations where safety regulations are being violated and to continue drawing the highest possible pay while the problem is being rectified. It is quite inconsistent to exhort miners to be more careful while at the same time subjecting them to economic pressures to cut corners.

The more things change the more they stay the same

81 miners working the same seam were killed under similar circumstances nearly 100 years earlier than the Appin disaster. You’d have thought the lesson was already there…but memories fade, times and technology change. We sometimes believe the illusion that we are better than our forebears.

The Appin Coal Mine Disaster has provided a timeless legacy and valuable lessons to the mining industry. Those lessons extended to Government’s companies and mine workers.

The disaster taught us that Governments must be timely in reacting to conditions that could cause the death of mineworkers, Companies must balance safe production and shareholder interest against employee safety, Employees and supervisors should not be clouded by production bonuses…lest those bonuses may cost lives.

It seems true though in 2019, that it still takes a disaster to get Government’s to look at problems that they knew of, and should have looked at, in the years before.

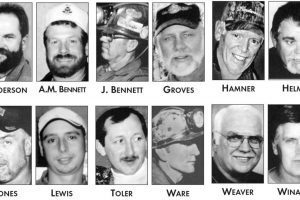

Names of the fallen

Alwyn Brewin (37), Francis Garrity (37), Ian Giffard (36), Geoffrey Johnson (35), Jurgen Lauterbach (30), Alexander Lawson (35), James Oldcorn (58), Peter Peck (36), Robert Rawcliffe (45), Roy Rawlings (31), Karl Staats (48), John Stonham (41), Roy Williams (27), Gary Woods (30).

Further Reading

Appin Mine: a day that shook our world (Brett Cox, 23 July 2009)

Appin Colliery explosion reassessed, Bob Kininmonth, Retired Senior Inspector of Coal Mines, Faculty of Engineering, Coal Operator’s Conference, University of Wollongong, 2010

Appin – 1979 Explosion, news item, 24 July 2018

To Punish or Persuade: Enforcement of Coal Mine Safety

Appin Mine Disaster, 24th July, 1979, Volume 2

Read more Mining Safety News and the latest in Mine Safety History

24 July also marks the anniversary of the South Bulli Disaster (Southern District of NSW), that occurred in 1991 and resulted in three fatalities – Robert Coltman, Leigh Pearce and Craig Broughton. These fine gentlemen perished as a result of a Carbon Dioxide gas outburst – night etched in my memory. The coroner found many failings on the part of the company and the recommendations forever changed the way underground roadways were developed in the Illawarra and Southern Highlands coal mines.