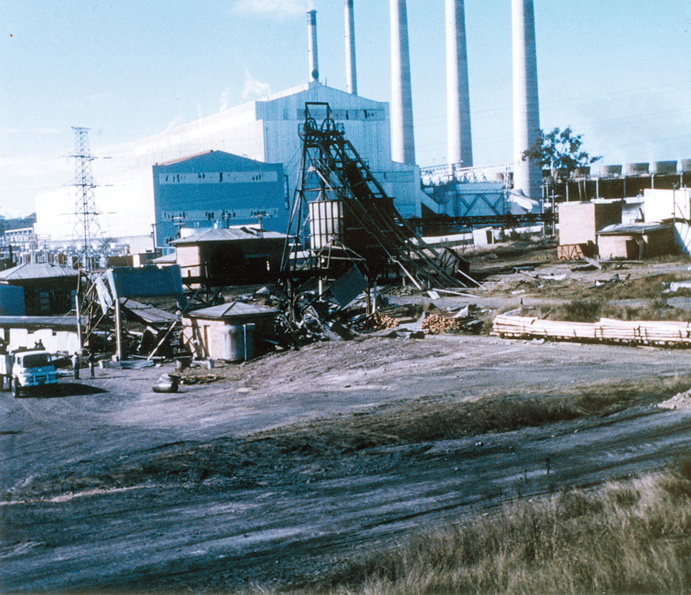

Located in Swanbank near Ipswich, Queensland, is the now dormant Box Flat colliery. Just over 42 years ago the coal mine was fully operational, having been opened a mere three years prior in 1969 – but due to an accident in the small hours of the 31st of July in 1972, it became the dreadful, burnt burial ground of 17 men, eight of whom were part of the Rescue Team.

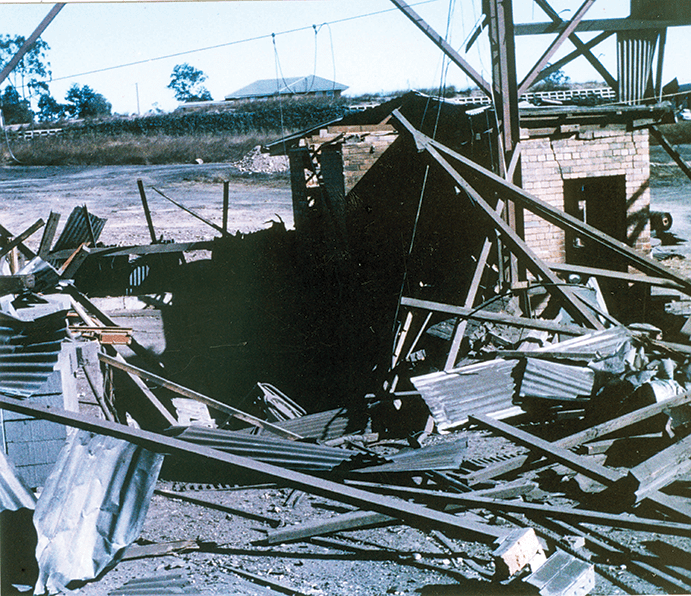

It was an explosion that saw both the men’s and part of the mine’s end, in addition to causing injuries to a further 14 mine workers, eight of whom were not even positioned underground, but rather at the conveyer belt entrances. One man, Clarrie Wolski, died some 14 months later in 1974 due to the terrible injuries he sustained. It was, as stated in the Mining Warden’s Court Inquiry that followed, “an explosion of considerable magnitude”.

In an interview with the Courier Mail in 2012, a former Ipswich miner, Beres Evans, told the newspaper it shook local homes. “We thought it was an earthquake,” Mr Evans said.

Sadly, the reason why the men were inside the mine at 2:47am on 31 July – a Monday – is the textbook trigger to call for evacuation in today’s mines. The team were attempting to put out a fire that was first noted by mine manager Alex Lawrie. He had informed Inspector of Mines Reg Hardie of its existence around 6 pm on Sunday afternoon.

The fire, which was first declared as being about 3-4 square feet in area, soon grew to be a ferocious monster, as observed by Mr Lawrie, Mr Hardie and a number of others when they went down into the mine to assess it as a group. They all returned to the surface around 10:20 pm, after being advised that there was smoke coming down the intake. To Mr Hardie, the presence of smoke meant there might have been an issue with re-circulation.

Don Livermore, working as an electrician at the mine that year, in 2009 described the incident from his perspective in an interview with Margaret Cooke of the Haencke Foundation (a foundation for the awareness of coal mining history in the Ipswich area).

READ RELATED CONTENT

- Written in Blood | The Moura Mine Disaster

- They took the risk and paid the price | Mount Kembla reflections

- Australian mining | A short history

“We went out and we were asked to put together a team as quickly as possible. There were other people there from the Rescue Brigade who’d got there before, and they’d gone down with their suits, and there was smoke coming behind them … we were to take breathing apparatus, extra breathing apparatus, down with us to give to the people that didn’t have a breathing apparatus so that they could come back out. They were concerned that the smoke was going to overcome [the others],” Mr Livermore said.

Between about 11:15pm-1:20am, a number of attempts were made by Mr Hardie and the team to stifle the fire, including two attempts to correct the position of a pair of doors within the mine that were seen to be causing a pressure differential along the return airway in No. 5 mine. The pressure differential was what caused the smoke, seen earlier. In the first attempt, Mr Hardie and the others tried simply walking down No. 5 mine to the doors, which were located about 36m out-bye of the underground towage, but smoke smothered their efforts. The second attempt employed the use of breathing equipment and travel via the pit bottom, though again, to no avail.

“A mine is perhaps salvageable, but lives, as the families and friends of those killed know so well, are not.”

It was soon realised that, in order to reach the fire, they would have to find an alternative route. A decision was made that in order to put the fire out, stone drives 5-7 would have to be temporarily sealed. The issue here is that the drives were located a depressing 450m beneath the earth, where there was already a significant build-up of gas and smoke. To get to them, the miners planned to enter via No. 7 mine, travel down and do what they could. It was at this point that, for the last time, a team of men would enter the mine – with every sadly misguided intention of returning to their respective families.

Fortunately for Mr Livermore, the position he found himself in during the explosion meant he would see his family again. “At the time of the blast I was in squatting position at rest in the north-west corner of the deputies cabin on the bench situated there, I was unhurt … I was the only one in there that wasn’t injured in some form. There was John Hall. He was on the floor under a lot of broken roof timber, and I didn’t see him at first. I went out the window because the window had been blown out, and of course, the first thing I wanted to do was get away from there.

I took a few steps, running away, and there was a fellow behind me – Graham Smith, I think it was; he was another Rescue Brigade bloke –he’d been outside and he was injured, and he needed help … so I ran back and stuck my head through the window that I’d just jumped out of, and here’s Clarrie Wolski leaning on the bench … Clarrie was a pretty tough bloke, and he’s standing there, and I said to him, “Are you all right, Clarrie?” He said, “No,” he says, “My pelvis is all busted. I can feel all the bones grating,” Mr Livermore explained in the interview.

After the blast, full rescue operations were deemed pointless due to the strong belief that none underground could have survived the blast, and so the decision was made at an executive level to seal off the mine permanently. Interestingly, Chief Inspector of Mines, Bill Roach, whose nephew was John Roach, one of those killed, made the call.

“…The general consensus was one of deep concern for the seeming inability of any worker involved in the accident to, at any time, query whether the men were pursuing the correct course of action…”

The inquiry into the disaster listed six main causes as to why the incident happened, quoted as follows:

- A spontaneous heating occurring in a pile of fallen coal in No. 2 level of No. 2 South Section in No.5 mine of Box Flat Extended Collieries on the weekend of 29th/30th July, 1972.

- This heating was assisted by the eleven-hour fan stoppage, during which period the reduced air flow allowed the heat generated to accumulate to a point of self-ignition.

- Fumes from the fire became evident in the intake airway.

- This heating developed into a large fire, which was assisted by the increased airflow when the mine fan was started.

- Efforts to extinguish or seal the fire were unsuccessful.

- An explosive mixture of gases generated from the fire, and possibly accompanied by water gas, was ignited. Coal dust was active in the explosions that propagated throughout the mine.

Put simply, the timing of the coal’s spontaneous heating within the mine could not have been worse – if the fan stoppage had not been in place, the temperatures probably would not have reached the level they did and thus, the fire never would have ignited, as emphasised in reason number two.

Overall, however, the Box Flat disaster was attributed to the combined power of two fundamental reasons that lean on each other. The first is the issue of re-circulation and the role it played in the unfortunate event. Recirculation is defined as being any amount of mine air flow that passes through the same area twice or more, leading to unwanted and often dangerous situations, including a build-up of heat and humidity, of fumes and coal dust, and, of course, flammable gases. It is deadly. Shortly before the explosion, John Roach, a member of the mine’s Rescue Team, rang those at the surface to say that smoke had backed up against the air intake, where not long before airflow had been fine. Now it just wasn’t moving. Preventing re-circulation is critical to mine safety, making both the measure and control of circulation and air quality of the utmost importance.

The inquiry states: “There is little doubt in our minds that re-circulation played a most important part in the events that night. It is clear that it was present at an early stage; certainly hours before the explosion. Apparently, the significance of this condition did not impress itself on the minds of those responsible for the conduct of operations, or, if it did, they did not accurately assess the potentiality of danger arising from it…”

Since re-circulation was an established problem in the mining industry and well known to mine workers the world over many years prior to the Box Flat disaster, the warden’s inquiry pursued the re-circulation issue. Questions were asked surrounding the thought processes and conduct of all those involved, including the men down the shaft, the manager and the inspector, and it was of particular interest to the inquiry to find out why the fire was not treated as a potentially fatal explosion. While it was concluded that no single person was at fault, the general consensus was one of deep concern for the seeming inability of any worker involved in the accident to, at any time, query whether the men were pursuing the correct course of action in attempting to extinguish the flames.

“… It must be observed that it appears that no one questioned the course of conduct proposed, from which it follows that all present were apparently in agreement with the assessment of the position made by the manager, the Inspector of Mines and other members of the team when they conferred from time to time. There were other experienced men present, who were aware that re-circulation was taking place, but it seems that they did not direct their minds to the potential danger of explosion inherent in this condition; rather, it seems that they were more concerned with the danger of being overcome by smoke and gases contained in it.”

“… the fact remains that not a single person put forward a contrary proposal at any stage.”

Some months later when the Box flat mine disaster inquiry’s results were released, a series of recommendations were made and eventually implemented in order to avoid there being another Box Flat disaster – in any mine. Some of these included:

The establishment of a Safety in Mines Organisation, designed to place emphasis on the practical demonstration of safety matters over theorised ones;

- A literature review of existing material regarding fighting mine fires be performed and senior personnel be advised on updates by a competent person;

- A review of the appropriate and proper treatment of flammable coal dust;

- Availability of gas-detecting equipment at mine sites as a preventative measure;

- Regular atmospheric sampling; and that provisions be made for the quick sealing of mines.

The proper treatment of flammable coal dust was especially stressed, due to the very real risk of it igniting. The rules outlined in the Acts and Regulations were, according to the Inquiry, not observed, though how spraying the coal dust with non-combustible or non-siliceous stone dust (a powder quite literally comprised of the dust of pulverised stone, sometimes containing soil or gravel) would have impacted on the Box Flat fire remains uncertain.

Inarguably, the most vital recommendation made by the Inquiry Warden on 7 November, 1972, was that all underground personnel should immediately be withdrawn from the mine once uncontrollable re-circulation of flammable gases is discovered. A mine is perhaps salvageable, but lives, as the families and friends of those killed know so well, are not.

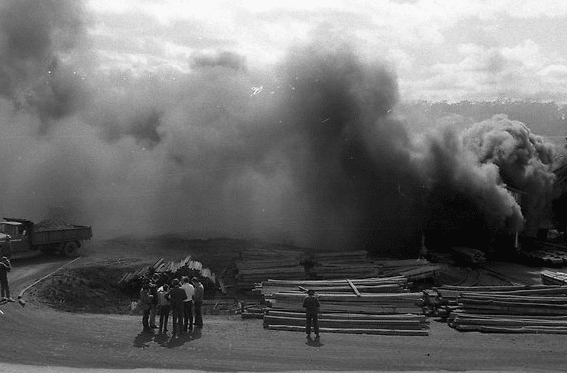

In the days and weeks following the Box Flat mine disaster, thousands attended the funerals for each of the deceased in various churches and buildings around Ipswich, but a service for all those killed in the accident, which saw local, state and federal representatives, the Queensland Governor, and about 150 miners, including the survivors, was held outdoors, smoke still billowing from the destroyed mine.

In 2012, on the 40th anniversary of the disaster, family and friends of the deceased again gathered to commemorate the tragedy, still a raw wound for many. As a former Ipswich Mayor highlighted, as stated in the Courier Mail, that 40 years is a long time, but for relatives and associates of the lost miners, it feels recent.

“At 2.45am on that day of horror, in an instant, husbands, fathers, sons, friends, neighbours, had their lives cut short. This monument serves here are to let their families know they are not alone, and their memory will never be forgotten by a city they gave so much to

Former Ipswich Mayor, Paul Pisasle on the 40th Anniversary of box flat mine disaster

Today, a memorial plaque and statue for the Box Flat mine disaster can be viewed at the mine site, on Old Swanbank Road, Ipswich.

LIST OF THE DEAD

17 miners died in the disaster and another died a year later as a result of injuries from the disaster.

There were six main causes of the disaster identified in the inquiry. Spontaneous combustion of coal appeared to be the catalyst of the disaster.

It is located at 252-254 Swanbank Road, Swanbank near Ipswich Queensland. https://www.google.com/maps/place/Box+Flat+Memorial/@-27.7139342,152.8648389,13z/data=!4m5!3m4!1s0x6b96b540af777c69:0xeeaebb68cf825fd8!8m2!3d-27.657126!4d152.808137

Following is a list of the miners who perished on that fateful day:

Kenneth Frank Cobbin

William Alexander Drewett

William Rae Drysdale

Andrew Charles Haywood

Robert Lloyd Jones

William Alfred Marshall

John James McNamara

Walter Michael Murphy

Brian Henry Randolph

Brian Rasmussen

Daryl Trevor Reinhardt

Harold Charles Reinhardt

John Dudley Roach

Lenard Arthur Rogers

Maurice John Tait

Mervyn Verrenkamp

Walter Benjamin Williams

Clarence Edwin Wolski died in 1974, due to the injuries caused in the explosion.

RESOURCES

Mining Inquiry – Box Flat Colliery: Report, Findings and Recommendations

The Haencke Foundation – http://www.haenkefoundation.org.au/~haenkefo/images/DonLivermore.pdf

The Queensland Times – http://www.qt.com.au/news/an-explosion-that-tore-through-ipswichsheart/1485221/

Add Comment