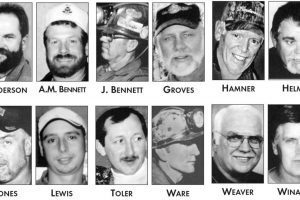

It was a known fact that gas was present in the Mt Kembla coal mine, yet miners strapped on their helmets with a naked flame burning bright that risk resulted in an explosion that killed 96 men on July 31, 1902 and continues to go down in history as the worst mining disaster in Australia.

Henry Lee and colleague Stuart Piggin wrote The Mount Kembla Disaster, in 1992. The following is Henry’s reflection on researching and writing the book and lessons to be learned from the disaster.

A REFLECTION ON THE MT KEMBLA DISASTER

The Mount Kembla mine disaster, which killed 96 men and boys on 31 July 1902, remains Australia’s greatest peacetime disaster on land. When Stuart Piggin and I began writing our book on the disaster, I sought answers to two questions. First, what caused the disaster? Second, what did those who owned, worked in, and regulated the NSW coal mining industry do to prevent a recurrence, at Mount Kembla, or at any other mine?

My attempt to find answers demonstrated the danger of relying on assumptions and, so-called, ‘common knowledge’. My own assumptions about Mount Kembla had three sources: the main Wollongong newspapers (the Illawarra Mercury, and the old South Coast Times), the Miners’ Federation newspaper (Common Cause), and my own prejudices. As each anniversary of the disaster approached, the papers retold the story, often in detail, and frequently accompanied it with accounts from disaster survivors.

The tale that evolved in these reports was simple and compelling. A synthesised version goes like this. Before the disaster, the existence of gas in the mine was common knowledge among both management and men. Both knew of the potential for disaster because the miners worked with naked lights (the lame from a wick, fuelled by il in a small pot carried on the front of the miner’s cap). Management knew of the danger because the miners frequently reported the occurrence of gas. Management, representing the mine’s shareholders, had a reckless disregard for the miners’ safety. The miners had to use naked lights, because the expense of providing them with the locked and enclosed safety lamp, invented nearly a century earlier, would have eaten into the owners’ dividends. In the afternoon of 31 July 902, the lives of 96 men and boys were sacrificed to the greed of proprietors who valued profits above human life.

Nonetheless, the disaster tradition continued, these lives were not sacrificed in vain. The lesson was learned, and mine proprietors, their managers, and the men gave an elevated priority to safe working conditions. The Parliament of NSW, and the Department of Mines, after a prompt and thorough investigation of the disaster, strengthened the legislation and procedures that regulated safety in the State’s coal mines. Among many improvements, Parliament, of course, ensured that, after Mount Kembla, NSW miners were never again forced to work with the cheap and dangerous naked light.

Not all of the above elements appear in any one version of the popular disaster tradition. Common Cause, for instance, denied that the disaster altered the priorities of owners or managers, and it was keener than the ‘capitalist press’ to emphasise shareholder greed and management disregard of safety. Of all the individuals associated with the disaster, it identified the mine’s manager, William Rogers, as the principal villain. There was, though, a tendency elsewhere to do the same. The disaster had brought Rogers before a judicial inquiry, which suspended him from duty. The disaster’s cause, therefore, was clear: an incompetent manager, acting for the faceless, distant and heartless shareholders of a mining company registered in London.

This looked fine, and it seemed a relatively straightforward matter to expand on and document the popular tradition from the contemporary sources. The Wollongong and Sydney press covered the disaster in great detail. Among other official records, three formal inquiries had produced reports and transcripts of evidence, which were supplemented by the archival records of the Coal Fields Branch of the NSW Department of Mines.

In fact, in the mid-1970s, when Stuart initiated an academic study of the disaster, the popular tradition was so well-known and accepted that little priority was given to its examination. Stuart’s aim was more an historical and sociological account of the disaster’s impact on the memory and values of the Mount Kembla community. To evaluate this, Stuart assembled a small group of academic historians and sociologists. The result was two articles in an Academic Journal. These concluded that, in the late 1970s, the disaster had meaning for very few of the inhabitants, in a community that no longer had a working coal mine. The group evaporated, leaving behind Stuart’s passion for writing a ‘complete’ account of the disaster. In 1982, he asked me to help him do so.

The more I read, the clearer it became that the popular tradition was, were accurate, simplistic and, on some important points, untrue. The first assumption to disappear was that establishing the cause of the disaster would be straightforward, meriting perhaps a short chapter. After all, it was common knowledge that the disaster resulted from the explosion of methane at a miner’s naked light. The event had been investigated thoroughly, over more than a year, by three official inquiries: an inquest, followed by a royal commission, and, finally, a judicial hearing on the conduct and competence of the mine manager. Surely, their findings, based on testimony from scores of witness and experts, drawn from every level of the industry, were authoritative and definitive. It remained only to craft their conclusion in to a crisp, concise account..

Not so. The inquest and the royal commission fixed different locations for the explosion in the mine, and their explanations for it differed in detail. Nonetheless, they agreed that the disaster resulted from the ignition of methane at a miner’s naked light.

There was, however, another theory, one that denied the presence of gas in Mount Kembla at all. Christened the ‘windblast theory’ by the royal commission, it was the child of Dr James Robertson, the influential, robust and ruthlessly cost-conscious managing director of the Mount Kembla Coal and Oil Company. His theory enjoyed support among mine managers from both the Wollongong and Newcastle coalfields. It predicated the disaster on the collapse of a huge, single expanse of roof, in a mined-out and abandoned 35-acre ‘goaf’, which propelled an enormous blast of air into the mine. This, Dr Robertson claimed, accounted for all the death and damage, and all the signs of charring and singeing on both corpses and equipment. The rapidity and force of the collapse, he said, had compressed the air below and raised its temperature to a point sufficient to ignite the clouds of coal dust raised by the blast of air that issued into the mine.

This theory suggested that the disaster was simply an unforeseen calamity, for which no one could be held accountable. Fencing off mined-out areas of a mine, and allowing the roof to ‘hang’ and gradually subside, was standard mining practice.

Neither the Doctor nor his theory, however, commanded universal support. The three NSW miners’ unions, on the Wollongong, Newcastle, and Lithgow coalfields, condemned it. The aim of the local union, the Illawarra Colliery Employees’ Association, was to pin the disaster on the Mount Kembla officials, especially the manager, William Rogers. This established, the union intended to issue the Company with writs, under the Employers Liability Act, to compensate the injured and the relatives of the dead. It seemed that the union would have its way. At the inquest, held immediately after the disaster, Rogers proved a poor witness, unable to counter claims by his miners that the seam not only gave off gas, but that, using their naked lights, they had lit ‘blowers’ (gas issuing from fissures in the coal seam) in his presence. when they reported the presence of gas to management, said the miners, nothing had been done.

If this was accepted by a royal commission or other official inquiry, then the Company was in trouble. The cost to it of a successful compensation action under the Employers Liability Act, would have been about £35,000. Up to March 1903, with the royal commission having two months to run, and a judicial inquiry into Rogers still to come, the Company’s legal bill alone totalled £10,000. There was also the cost of rebuilding and re-equipping the damaged mine. With only £25,000 in the contingency and reserve fund, the Mount Kembla Company’s shareholders, mostly wealthy investors who lived in London, faced the loss of heir dividends for some time.

If this was accepted by a royal commission or other official inquiry, then the Company was in trouble. The cost to it of a successful compensation action under the Employers Liability Act, would have been about £35,000. Up to March 1903, with the royal commission having two months to run, and a judicial inquiry into Rogers still to come, the Company’s legal bill alone totalled £10,000. There was also the cost of rebuilding and re-equipping the damaged mine. With only £25,000 in the contingency and reserve fund, the Mount Kembla Company’s shareholders, mostly wealthy investors who lived in London, faced the loss of heir dividends for some time.

That was why Robertson manufactured the windblast theory. The Coal Mines Regulation Act required management, whenever it became aware of dangerous gas levels, to substitute locked safety lamps for naked lights. If, however, there was no gas in Mount Kembla, then management negligence or incompetence did not arise. No case could be made against any of the officials and, thus absolved of even indirect responsibility for the disaster, the Company could not be subjected to an action under the Employers Liability Act.“

“There was incontrovertible evidence, from miners and Department of Mines inspectors, that the seam constantly exuded small quantities of gas.”

FEATURE LESSONS FROM THE PAST

Here was a story that demanded more than a grasp of early twentieth-century mining terminology and practice. That was essential, but the story of the disaster began to take shape as a more universal tale of human and institutional self-interest. In this context, the ‘truth’ of the disaster was a political matter.

Here was a union, the Illawarra Colliery Employees’ Association, whose General Secretary, David Ritchie, brought to the disaster a grudge against mine management in general and that of Mount Kembla in particular. Virtually all mining families on the Wollongong coalfield had suffered great deprivation in the depression of the 1890s, and the industrial turmoil that accompanied it. Ritchie, who then worked at Mount Kembla, was victimised by the Company and, with his family, reduced to penury. By 1902 economic recovery had returned profitability and steady employment to the coalfield, which allowed the resurrection of the union. The Mount Kembla Company and its managing director had been the union’s most intransigent enemies, and the disaster gave Ritchie and his union the opportunity to lay Dr Robertson, William Rogers and their Company. Wielding the Coal Mines Regulation Act in one hand, and the Employers liability Act in the other, Ritchie smelt corporate fear.

The measure of that fear was the windblast theory. Its ascendancy was short lived, and it did not survive the royal commission. The only element accepted by the commission was that the disaster originated with the collapse of a section of roof in the 35-acre goaf. There was incontrovertible evidence, from miners and Department of Mines inspectors, that the seam constantly exuded small quantities of gas. Before the disaster, that knowledge was Mount Kembla’s worst kept secret, and the inquiries established that both miners and management had engaged in a conspiracy of complacency. In 1902, as they enjoyed the beneits of economic recovery, neither masters nor men saw any point in stopping production for a little gas. The miners constantly lit blowers at their workplaces, and management knew that they did. They all invested their faith and their lives in a grand new furnace ventilation system that supplied the mine with an air current sufficient to sweep away any trace of gas.

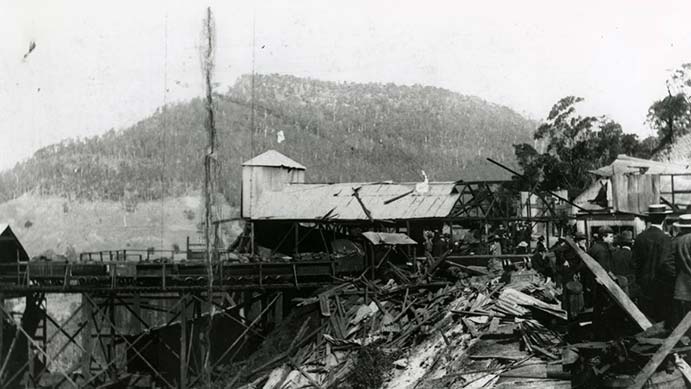

Unknown to them, for years, tiny traces of methane made their way into the 35-acre goaf, where they accumulated at its highest point. When the roof collapsed, just before 2 pm on 31 July 1902, it forced into the mine workings a mixture of air and methane that ignited at the naked light of the first miner it encountered. The initial explosion produced a series of other explosions, as the clouds of coal dust thrown up by the air blast from the goaf also ignited.

This was the finding of the royal commission, which was a thorough and comprehensive an investigation into a mine disaster as any undertaken anywhere in the world. The commission said it was the best explanation it could offer. It added that it could not explain every last indication of force, but that this was not unusual given the chaotic and catastrophic nature of the explosions.

The three commissioners were also unanimous, and more forcefully so, about Dr Robertson’s windblast theory. Even if they had been unable to conceive of another explanation, they stated, they would not countenance the windblast theory. The commissioners, one of whom was Daniel Robertson, James’ brother and managing director of the big Metropolitan mine at Helensburgh, at the northern end of the Wollongong coalfield, dismissed it as preposterous.

James’ and Daniel’s relationship demonstrated the subtleties in the response of the proprietors and their managers to the disaster. Although the two were brothers and managing directors of the two biggest mines on the coalfield, they did not get on. James’ approach to mining was entirely practical and devoted to limiting costs, to deliver the maximum profit to the shareholders. Daniel believed in these things too, but he loathed his brother’s belief that that was the limit of his duty.

A crucial point of disagreement was the issue of what constituted a dangerous level of gas in a mine. In 1902 there was no consensus on this among mining theorists or practitioners. The uncertainty was reflected in the Coal Mines Regulation Act, which contained no guidance on the matter. This was why even big companies like Mount Kembla were allowed to use cheap, and potentially dangerous, naked lights. It was standard mining practice. During the royal commission, though, Daniel Robertson stated that any trace of gas in a mine was dangerous and that he wanted naked lights banned. His own mine, the Metropolitan, had used safety lamps from the outset. If enforced across the industry, though, this would put companies to the expense of buying and maintaining locked safety lamps. This, he believed, was why men like his brother thought him a mad and radical visionary. For Daniel, though, it was a practical and sensible measure, which protected the shareholders’ investment; if the mine blew up, the repair bill was theirs. It was also compatible with his view that mining companies had a duty to protect the lives of their miners.

A crucial point of disagreement was the issue of what constituted a dangerous level of gas in a mine. In 1902 there was no consensus on this among mining theorists or practitioners. The uncertainty was reflected in the Coal Mines Regulation Act, which contained no guidance on the matter. This was why even big companies like Mount Kembla were allowed to use cheap, and potentially dangerous, naked lights. It was standard mining practice. During the royal commission, though, Daniel Robertson stated that any trace of gas in a mine was dangerous and that he wanted naked lights banned. His own mine, the Metropolitan, had used safety lamps from the outset. If enforced across the industry, though, this would put companies to the expense of buying and maintaining locked safety lamps. This, he believed, was why men like his brother thought him a mad and radical visionary. For Daniel, though, it was a practical and sensible measure, which protected the shareholders’ investment; if the mine blew up, the repair bill was theirs. It was also compatible with his view that mining companies had a duty to protect the lives of their miners.

James, on the other hand, was contemptuous of his employees. He trusted neither their judgement nor their commitment to their work, and he despised their community institutions, the trade unions, workmen’s clubs, and the like. When the medical doctors called by the royal commission established that the windblast theory could not explain the deaths of the men at Mount Kembla, Robertson, himself a medical man, made the utterly contemptible utterance that, if there was gas, the miners blew themselves up, while they were slacking in the mine, having a smoke.

The three royal commissioners, Daniel Robertson, for the employers, David Ritchie, for the miners, and Judge Charles Murray, for the government, would have nothing to do with such explanations. Other mine managers also ridiculed the windblast theory. In fact, the managers who supported it were Dr Robertson’s proteges and/or held positions in Wollongong and Newcastle mines under his control.

The three commissioners produced a magnificent, comprehensive and unanimous report, and recommended a multitude of reforms to mining practice and legislation. Its central proposition was that the only measure that could have prevented the disaster was the introduction of safety lamps. Allied to this was the grossly misplaced faith that management and miners had invested in the Company’s new furnace ventilation system. All concerned, said the commission, had been working in ‘a paradise of fools’. The commission stated that any trace of gas in a mine was dangerous, and that, when detected, naked lights should automatically be replaced with safety lamps.

The great shock, for me, was the response to the royal commission’s report. The Chief Inspector of Coal Mines, Alfred Atkinson, drafted several bills to amend the Coal Mines Regulation Act, along the lines recommended by the commission. None of them, however, survived the introduction stage. In 1903 the NSW Government was in the hands of the Progressive Party. It was, however, a minority Government, and when it introduced a bill to compel the use of safety lamps in mines, it was opposed by the Labor and the Liberal parties.

The ex-miners in the Labor Party led the charge against the safety lamps bill. My naive understanding of contemporary mining practice, made it inconceivable to me that the workers’ Party would block a measure designed to save miners’ lives. The Liberal Party’s opposition was to be expected; it refused to impose extra costs on mining companies when there was no standard for a dangerous level of gas in a mine.

Miners, it transpired, did not like working with safety lamps, for several reasons, but their underlying antipathy was based in the method by which they were paid. Miners were not paid a regular weekly wage. They worked on a hewing rate, which paid so much for each ton of coal that they cut. Payment by piece rates suited the employers, because, from the mid-nineteenth century, the NSW coal industry had developed a chronic capacity for overproduction. Coal powered the economies of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It fuelled railway locomotives, steamships, and factory machinery; in homes it cooked food, heated water, and provided warmth in winter. Good profits could be made from mining coal, during periods of economic growth. In such times, when coal fetched high prices, investment poured into NSW’s coalfields, progressively increasing the industry’s capacity for production. This produced a situation where, even in relatively good times, there were too many mines for the available demand. In turn, the proprietors clamped down on costs, the biggest of which was wages. There was no point paying miners to produce coal for stockpiling, in the hope that the company might secure a new or expanded steamship, railway or factory contract. That was why miners were paid piece rates. They allowed the proprietors to employ, and pay, miners, only when and as they were required.

Paying miners for their output, and not the time they spent in the mine, though, strengthened the miners’ ability to determine the length of their working day. This took the form of ‘the darg’, a work practice enforced by the miners’ unions to limit individual miners to hewing a fixed daily quantity of coal. This protected them against the greed of men who would cut coal without regard for their own or others safety. It protected the livelihoods of older and/or less efficient men, whom management might replace with younger, stronger and greedier men.

It also meant that, knowing the hewing rate, the miners could determine the quantity of coal that would give them a living wage. Once that quantity was cut, the men could leave the pit. This caused the miners to prefer naked lights to safety lamps. The former gave o a far brighter light, which allowed the miner to work faster and more safely. If a safety lamp went out, the miner had to stop work and trudge, perhaps miles, through the mine to the lighting station, where the lamp could be unlocked and safely re-lit. This meant lost time, effort, and earnings, not only for the miner whose lamp it was. Miners generally worked in teams of two. If a miner’s lamp went out, then his mate would also have to down tools, to illuminate the way back to the lighting station. If a naked light was extinguished, it could be re-lit immediately, with another naked light, or a match.

The miners’ unions would agree to the compulsory use of safety lamps only if the hewing rate was increased, to compensate them for the inconvenience, and the greater time spent in the pit to make ‘the darg’. Most owners refused to countenance an increase, or to be put to the expense of buying and maintaining the lamps. When, from the fear occasioned by the explosion at Mount Kembla, the Wollongong mines switched for a time to safety lamps, miners complained the loudest. Some quit the Wollongong mines because of them. They went to the Newcastle coalfield, whose proprietors, managers and miners believed that Mount Kembla had nothing to teach them about gas or naked lights.

The miners’ unions would agree to the compulsory use of safety lamps only if the hewing rate was increased, to compensate them for the inconvenience, and the greater time spent in the pit to make ‘the darg’. Most owners refused to countenance an increase, or to be put to the expense of buying and maintaining the lamps. When, from the fear occasioned by the explosion at Mount Kembla, the Wollongong mines switched for a time to safety lamps, miners complained the loudest. Some quit the Wollongong mines because of them. They went to the Newcastle coalfield, whose proprietors, managers and miners believed that Mount Kembla had nothing to teach them about gas or naked lights.

Alfred Atkinson and his Coal Fields Branch acted to have the NSW Parliament implement the royal commission’s recommendations. They failed, because the opposition of both proprietors and miners, which materialised in an unholy alliance between the Liberal and Labor parties, was too strong.

That was the overwhelming tragedy of the Mount Kembla disaster. The 96 victims died in vain, as the Parliament and the Government succumbed to paralysis. All of the Government’s proposed amendments to the Coal Mines Regulation Act were blocked by Liberal and Labor opposition, and Parliament did not consider any of the royal commission’s findings.

Instead, Alfred Atkinson and the Department of Mines, and the Illawarra Colliery Employees’ Association went after Mount Kembla’s manager, William Rogers. Atkinson was appalled that the industry had not heeded the lessons of Mount Kembla, and had stopped Parliament from implementing the commission’s recommendations. The union wanted to punish the Mount Kembla Company, one of its most intransigent opponents. The union also represented those miners and their families for whom it was important to make ‘someone’ accountable for the disaster. Most people could not begin to comprehend that the disaster’s roots were in the economics of the industry, and the lax attitude to safety that this engendered among all concerned. In 1902 times were good, and Mount Kembla was working at full pace. This, and the new furnace ventilation system encouraged both miners and management to ignore the danger from the traces of gas that mine constantly gave off.

“Times were good. Demand for coal was high, and work was plentiful. Why stop the production of profit it and wages for a little gas,that would be swept from the mine by a wonderful new piece of technology? They all took the risk, and at about 2pm on 31 July 1902, they paid the price.”

The miners and their union could have used the Coal Mines Regulation Act to have the government inspectors investigate every occasion on which they detected gas. That they did not, owed much to the pervasive attitude that a little gas was not worth bringing work to a halt, clearing out of the mine, and possibly having safety lamps introduced, if the inspectors thought it was warranted. No one among the proprietors, the management, or the workforce wanted that. Times were good. Demand for coal was high, and work was plentiful. Why stop the production of profit and wages for a little gas, that would be swept from the mine by a wonderful new piece of technology? They all took the risk, and at about 2pm on 31 July 1902, they paid the price.

The commission took pains to establish that, while there had been irregularities in the management of the Mount Kembla mine, and breaches of the Coal Mines Regulation Act, none of these contributed to the disaster. This ended the Illawarra Colliery Employees’ Association’s plan to use the Employers Liability Act against the Company. This only intensified the need to make someone pay a price for the dead. The records of the NSW Department of Mines, however, demonstrated that management practices at Mount Kembla were no better or worse than those at comparable mines. William Rogers simply happened to be in charge when one of NSW’s biggest coal mines blew up. He was to be made the scapegoat for Alfred Atkinson’s frustrated ambition to clean up mining practice and safety, and for those who wanted to punish the Company and make ‘someone’ pay for the disaster.

The Minister for Mines authorised a judicial inquiry into Rogers’ conduct, and his Department prepared a list of charges under the Coal Mines Regulation Act. An attempt by the miners’ union to blame management, principally Rogers, for the disaster, at both the inquest and the royal commission, had already failed. Consequently, the union abandoned its proceedings under the Employers Liability Act. Nonetheless, Alfred Atkinson wanted a severe punishment inflicted on Rogers, to put other NSW mine managers on notice that lax conduct would no longer be tolerated, and that it would bring dire personal and professional consequences.

The Department of Mines case against Rogers verged on making him responsible for the disaster, and the inquiry did find him guilty of several breaches of the Act. It found, however, as did the royal commission, that none of those breaches caused the disaster. The Judge, Charles Heydon, expressed his regret at having to impose on Rogers a 12-month suspension of his manager’s certificate. His regret was well-founded. Heydon noted that Rogers was a competent practical mine manager, who was guilty of offences that occurred daily in NSW coal mines. He said that it was Rogers’ misfortune that Mount Kembla exploded, causing an unprecedented loss of life, while he was the manager. The investigation of the explosion had uncovered breaches of the law, that were unrelated to the disaster. Had the disaster not occurred, the management irregularities at Mount Kembla would have continued, undetected.

Some Labor MPs, particularly the ex-miners, were unhappy that Rogers ‘got off’ with a suspension. Men like John Nicholson, a former Bulli miner and Independent Labor MP for the Wollongong coalfield seat of Woronora, wanted Rogers’ head. These were the same men who had rejected the more important recommendations of the royal Commission They were, however, so incensed at what they saw as Rogers’ mild punishment, that they fuelled a protracted and bitter debate, to have Rogers thrown out of the industry. It was a disgraceful performance by a group that, like their Liberal enemies, were unwilling to compromise to improve safety in the State’s mines.

Rogers was an easy target. My first impression of him, based on his testimony to the disaster inquiries, was that here indeed was an ill-informed and probably incompetent mine manager. At times he was barely coherent, and admitted to never reading reports or technical literature on mining. Moreover, he was a mine manager by virtue of a certificate of service. That is, he had never formally studied coal mining, and had no formal mining qualifications. This, however, was not unusual. Half of the managers of NSW coal mines held certificates of service, rather than the certificate of competency, gained by formal study.

Some contemporaries seized on Rogers’ bumbling performances at the inquires, as a justification for blaming him for the disaster. This ignored several things about Rogers. He was regarded, by proprietors and workers alike, as a competent practical manager. In the wake of the disaster, the man experienced something like shell-shock. Not only had the mine he managed blown up, killing many men that he knew personally; his adopted son, Tom Hughes, a miner, had perished in the disaster. Also, Rogers was not a native English speaker. Until he was in his twenties, he spoke only his native Welsh tongue. At the inquest and the royal commission, he was interrogated relentlessly by David Ritchie, the articulate General Secretary of the district miners’ union, who was personally hostile to both Rogers and the Company, and Andrew Lysaght, the union’s university-educated and aggressive solicitor. Lacking a formal education, rattled by the disaster, and coping with personal grief, it was little wonder that, when he appeared before inquiries that had the potential to blame him for the disaster, end his career and, perhaps, send him to gaol, he was less than impressive.

In any case, the breaches of the Act that Rogers committed would normally have been dealt with, as Judge Heydon noted, by a magistrate’s court, and a fine. As Heydon also noted, however, these were not ordinary circumstances, and he had to take that into account when deciding his punishment. In short, Heydon imposed on Rogers’ a ‘political’ sentence. This was an attempt to satisfy the clamour for Rogers’ head, from the Illawarra Colliery Employees’ Association and the Labor MPs, and to give Alfred Atkinson, in view of Parliament’s inability to strengthen the Act, an example for the entire coal industry.

It was unnecessary, unjust on Rogers, and an unsatisfactory and inappropriate conclusion to the inquiries into the disaster. The victims had been sacrificed a second time, to political and industrial expediency, and Australia’s worst peacetime land disaster failed to improve safety in the coal industry. In the aftermath, Atkinson made valiant efforts to get the NSW coal proprietors to agree to a voluntary and uniform safety code, that incorporated some of the royal commission’s recommendations.

These people and their Parliamentary representatives had already rebuffed a royal commission, and the State’s Parliament and Government, on these matters. Atkinson failed then, and he failed now. Naked lights would not be banned from NSW coal mines until 1941. This exploded the greatest of the myths in the popular tradition. A big disaster, in which many people die, does not necessarily translate into lessons learned, which are then applied to make a better world.

The monuments erected for the victims of the Mount Kembla disaster were the headstones over their graves, and the monument that now stands in the grounds of the Mount Kembla Soldiers’ and Miners’ Memorial Church of England. They also got a living monument, in the annual disaster memorial service in the Mount Kembla Anglican church. By the late twentieth century, however, the service remained relevant to only a few ‘true believers’, generally those with a family connection to the disaster.

The Mount Kembla mine closed in 1970, and in the 1980s a world-wide recession gutted Wollongong’s iron and steel industry, and the remaining coal mines that fed it. As manufacturing and mining gave way to service industries, Mount Kembla’s population resembled less and less that of 1902. A mining workforce community was replaced by a middle-class professional one, whose members’ employment took them to other parts of the district and even beyond it. In 1992, in the conclusion to The Mt Kembla Disaster, we took the view that the annual commemoration would probably die out, as a consequence of these economic and demographic changes

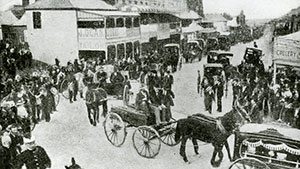

The centenary of the disaster, in 2002, however, re-ignited the community’s interest. A strong and energetic local committee invested itself in planning and promoting the commemoration of the centenary. It attracted State and national media attention, and the local television station, WIN TV, produced a documentary on the disaster. A succession of commemorative events was held at Mount Kembla, and these brought to the village record numbers of people, from the Wollongong district and beyond.

It is early days, but the committee has probably rescued from oblivion the disaster’s living tradition. The 96 men and boys killed on 31 July 1902 were treated shamefully by the economic and political system that they served. That system buried quickly and effectively the recommendations of the royal commission that, if accepted, would have saved many lives lost in subsequent disasters. The Mount Kembla victims deserved an acknowledgment that they were never given. The system not only did not learn from their deaths; it wilfully ignored them.

In the popular tradition, though, there was always a desire to give greater recognition and meaning to those who perished. That desire created a seeming paradox, for, as the popular tradition evolved, it granted the victims an acknowledgment and an influence that never existed.

This manifested itself poignantly and repeatedly in one of the tradition’s central myths, that the disaster forced major improvements in mining safety. This was no better expressed than by K C Stone, a Mount Kembla resident, in his booklet A Profile History of Mount Kembla, privately published in 1974. He wrote at the end of his account of the disaster that, ‘Only by the sacrifice of many lives … was the way paved for better conditions for miners. A natural outcome … was the introduction of the safety lamp’. It should have been so, but it was not.

The publication in 1992 of The Mt Kembla Disaster, added another memorial. Stuart and I believed that we had at least set the record straight, and did justice to the memory of those sacrificed in the disaster. Nothing can change the reality that their sacrifice was ignored by the government and the industry, neither of which took any lessons from it. The disaster failed to change the conduct of the industry. In that light, the men died for nothing.

The Mount Kembla victims were denied the best memorial: contemporary acknowledgment, through the reform of mining practice and legislation, of a sacrifice they should never have been compelled to make. Inscriptions on headstones and monuments erode and fade with time. Commemorative church services lose their force, as society becomes more secular, as memories fade, and as ‘oldtimers’ die or move on. Books, unless they engage the living, rest, unread, on shelves.

The achievement of the Mount Kembla Disaster Centenary Committee is to renew and revitalise that engagement. It is early days, but the preservation of the disaster, as a living tradition seems assured for some time yet. It serves to keep alive a story of how institutional self-interest obliterated and demeaned the needless and unwilling sacrifice of 96 lives at Mount Kembla on 31 July 1902. That, for my part, is the essential story of the Mount Kembla disaster, and, although it concerns a little mining village on the fringe of the British Empire, it is unlikely to lose its relevance before its bicentennial commemoration.

Henry Lee, ‘A reflection on the Mt Kembla Disaster’, Illawarra Unity, volume 3, issue 1, 2003, pp.33-45. To read the full reflection, visit http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1099&context=unity

PROFILE

Dr HENRY LEE

Henry Lee has been the Academic Program Manager at UOW College, University of Wollongong, since 2008. In that role he oversees the operation of the College’s university pathway and higher education Diploma courses. Henry holds a PhD in History from the University of Wollongong and lectured there in the Faculty of Arts, in History and Politics, and then in the Faculty of Commerce, in Industrial Relations, before joining UOW College. His 1993 PhD thesis traced the development of the coal industry in the Wollongong district of New South Wales, and he has published material on Wollongong’s economic and political history. He is the co-author, with Stuart Piggin, of The Mt Kembla Disaster, published by Oxford University Press in 1992.

Henry Lee has been the Academic Program Manager at UOW College, University of Wollongong, since 2008. In that role he oversees the operation of the College’s university pathway and higher education Diploma courses. Henry holds a PhD in History from the University of Wollongong and lectured there in the Faculty of Arts, in History and Politics, and then in the Faculty of Commerce, in Industrial Relations, before joining UOW College. His 1993 PhD thesis traced the development of the coal industry in the Wollongong district of New South Wales, and he has published material on Wollongong’s economic and political history. He is the co-author, with Stuart Piggin, of The Mt Kembla Disaster, published by Oxford University Press in 1992.

READ RELATED CONTENT

Add Comment