Professor David Cliff writes about OHS in the minerals industry in the 21st century.

Great progress has been made in reducing accidents and incidents in the mining industry. Large highly mechanised mines, employing relatively small workforces, have achieved significant reductions in fatality and injury frequency rates.

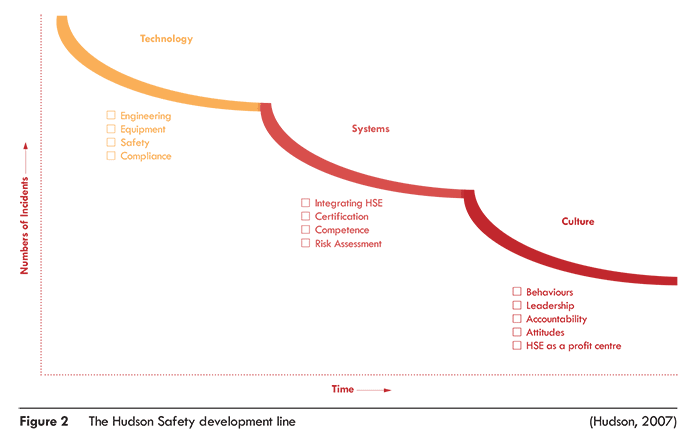

There is no doubt that through the implementation of technology and through gaining an understanding of major mining hazards, we have reduced the incidence of multiple fatalities. The last fire or explosion in an underground coal mine that caused fatalities was in 1994. Australia went over 10 years without a multiple fatality event (from 2000 to 2013).

The implementation of safety management systems, risk management, workforce representation and duty of care, and process-based legislation have been credited with making Australian mining the safest in the world.

The implementation of safety management systems, risk management, workforce representation and duty of care, and process-based legislation have been credited with making Australian mining the safest in the world.

Sophisticated incident investigation techniques that allow us to drill down to the underlying causes have assisted in developing safe systems of work. These underlying causes do not always rely on an error by the person who was harmed. We now recognise the importance of external factors such as the organisational culture, the work environment, the physical environment and the actions or inactions of others.

The current low commodity prices place immense pressure on mines to improve productivity and reduce staffing. This in turn can lead to a reversal of the safety culture improvement through the focus on doing what has to be done rather than what should be done.

Technology, systems and culture all require continual effort and adequate resourcing to be effective. Reducing the effort or resourcing risks increases the health and safety risk. The low fatality rate breeds complacency, and personnel can assume that the hazards are not real as they have not experienced them themselves. This in turn leads to underestimating the risk and the need for controls.

In the past two years in Australia, there has been a spate of fatalities and the rate is much higher than for the previous four years, this may just be coincidence or a warning of things to come.

The Pike River Coal Mine disaster where 29 miners lost their lives in 2010 (Royal Commission, 2012), is seen as a classic example of failing to recognise the hazards. With limited resources there is a tendency to retreat to rules and compliance – compliance, of course, aims to ensure a minimum standard, not best practice. There is a need for companies to reassert their commitment to the health and safety of workers and ensure that no corners are cut.

Effective safety and health management systems require continual vigilance to ensure that the systems are being implemented as designed and are achieving the desired outcomes. This monitoring and review process requires personnel, resources and management commitment.

New technology will be introduced to improve mining and mineral processing, but unless how it works is properly understood, we run the danger of creating new risks not from malfunctioning systems but from complex systems functioning as designed just not as predicted (Dekker, 2011).

The recent accident between an autonomous haul truck and a water cart is an example of this. The autonomous haul truck performed as it was programmed, however the driver of the water cart was not aware that the vehicle was about to turn across its path.

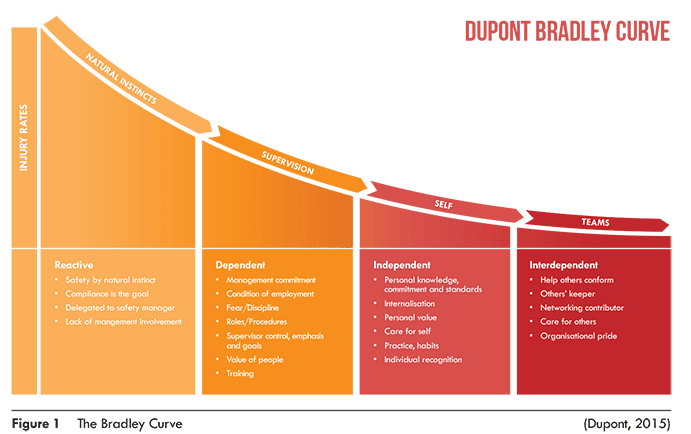

To avoid this we need to focus on the right hand side of the safety culture diagram (figure one) and recognise that the workforce is an asset that needs to be nurtured.

Fiedler (1984) demonstrated that working on productivity and safety cooperatively improved both. All those attributes listed under the Independent and Interdependent categories are not exclusive to OH and S. They apply equally to effective production.

McLain and Jarrell (2007) investigated the outcomes of compatibility between safety and production. In line with theory, this research suggested that safety production compatibility (and thus conflict) was linked to safe work behaviours and the extent to which hazards interfered with tasks performed.

The financial benefits of good Occupational Health and Safety performance are well-documented. The costs include not only the direct costs but also the hidden costs, which can be up to 200 per cent of the direct costs (Oxenburgh, 1991).

Thus it would be argued that reducing accidents and illness makes good financial as well as ideological sense. It is not just time away from work that reduces productivity, but also presenteeism – where one is at work but not functioning at full capacity.

Williden et al (2012) showed that workers affected by stress and anxiety while still at work, have reduced productivity by over 10 per cent. Presenteeism can multiply the real cost of an illness by up to four times (Geotzel et al, 2004).

As well as causing illness and lost productivity, work stress has also been shown to influence employee safety through a number of mechanisms. Masia and Pienaar (2011) found that work stress had an inverse relationship with safety compliance, as they did for job insecurity.

In addition, several studies by Maiti and colleagues have suggested that job stress encourages employees to avoid safe work behaviours, thus increasing their likelihood of workplace injuries, and that job stress can indirectly lead to employees becoming less job-involved, which may also increase their likelihood of injury as greater job involvement is associated with better safety performance.

Conclusion

The twenty first century poses many challenges to the improving the health and safety performance of the world-wide mining community.

In some ways, the recent success in reducing the fatality rate in mining in developed countries is its own worst enemy as it can breed complacency. Couple this with the pressures to reduce cost and improve productivity and there is a real danger that the health and safety performance in developed countries will get worse rather than better.

It is essential that we fully understand how new technology works and the full implications of its operation.

Mining will continue to be impacted by low commodity prices leaving less money to spend on discretionary items. The challenge is to not make good health and safety optional, but a normal part of the way of life.

David Cliff

David Cliff

David Cliff was appointed Professor of Occupational Health and Safety in Mining and Director of the Minerals Industry Safety and Health Centre (MISHC) in 2011. His primary role is providing education, applied research and consulting in health and safety in the mining and minerals processing industry. He has been at MISHC over fourteen years.

Previously, David was the Safety and Health Adviser to the Queensland Mining Council, and prior to that manager of mining research at the Safety In Mines Testing and Research Station. In these capacities he has provided expert assistance in the areas of health and safety to the mining industry for over twenty-six years.

He has particular expertise in emergency preparedness, and fires and explosions, including providing expert testimony to the Moura No 2 Warden’s inquiry, the Pike River Royal Commission and the Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry. He has also attended or provided assistance to over 30 incidents at mines involving fire or explosion.

David has extensive experience in providing training and education in OHS in mining to in many countries.

He has published widely in the area of occupational health and safety in mining.Australian mining companies a platform to confidently make decisions to maximiSe efficiency and safety, both in real time and planning for the future.

Add Comment