The entombed miner is a story of a Western Australian mines rescue initiative that saved a mineworker in the midst of adversity.

More than a century ago, a small mining community was rocked by a terrifying thunderstorm which left a miner trapped underground due to heavy rain filling the mine.

The water wasn’t the only thing overflowing, with a flood of camaraderie and loyalty during a gruelling nine-day rescue took place to save the entombed miner.

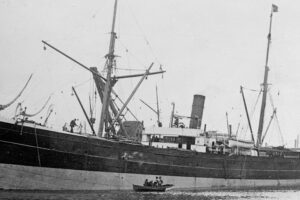

On March 19, 1907, the storm burst over the Coolgardie goldfields in Western Australia, with the underground gold mine at Bonnievale going underwater.

All 160 miners scrambled to safety, with the exception of Italian mineworker Modesto “Charlie” Varischetti, who had been working alone in a 30ft rise from the 1000ft level.

At first, Varischetti was assumed dead, but local Inspector Josiah Crabb, thought there may have been a possibility the man was alive, with air in the stope potentially preventing water from filling. In twelve hours, the water had only gone down nine inches, and it was feared the slow descent of the water would see the man starve to death.

A telegram to Perth – “Man in rise twenty-eight feet below level; only thing can be done is to supply food by means of a diver; can one be produced? If so, please send him and all necessary appliances as soon as possible”.

The telegram would be the beginning of a heroic and memorable rescue, which would go down in history as a tale of bravery, mateship and determination.

Varischetti, a 32-year-old father from Gorno in Lombardy, had lost his wife when she gave birth to their fifth child. The Catholic Church suggested he go to Australia, where mining work was plentiful, and he could send home his earnings.

The Barrier Miner reported on Saturday, March 30, that Varischetti said:

“he rushed towards the shaft, but the water seemed to gather force with depth, and it bore him backwards four times. When the water had risen to his chin he retreated up the rise and and resigned himself to death. Here, with only a stone to rest on and about 40ft of space length to move in, Varischetti began a period of horror and suspense. He was resigned to his fate, not daring to hope for rescue. He could not tell how long after it was when he heard blows on the rock somewhere above him. He responded, and then he hoped for life.”

While he was trapped for nine days, Varischetti was not alone.

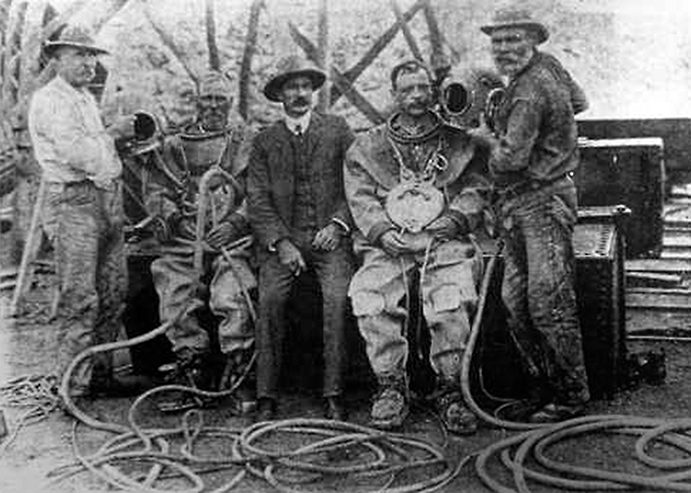

Four divers – Hughes, Fox, Hearne and Curtis arrived two days after the Inspector’s telegram was sent. The next day, Hughes went sent down the mine.

Hughes went down into the mine three times without getting further than No 10 level – it wasn’t until his fourth attempt that he reached the beginning of the rise, wading through water in treacherous conditions, and on the fifth attempt, he reached Varischetti and gave him food. He later recalled that Varischetti was crouched in the darkness, initially frightened at the sight of Hughes.

Mines rescue initiative

He made the perilous journey, again and again, delivering food, lights and conversation on a daily basis – keeping the man in high spirits until the water lowered to a safe level. The Barrier Miner reported in the same article, that Hughes stated the water was higher than he expected.

“He had made four trips altogether, having to swim the first time. Varischetti met him, and they chatted for over an hour. Jokes were cracked and cigarettes smoked.”

On the ninth day the water was finally low enough. A crowd had gathered at the shaft mouth, with the Inspector Crabbe telling the media that Hughes, and his fellow divers Hearne and Curtis, were heartily cheered on going down to the No 9 level – mine water was lapping the roof of the No 10 level, a sign that the 10-day struggle was drawing to a close.

During the final rescue, a shot was fired to blast away an obstruction, and many requests were received at the surface for different materials. The same day, the divers resurfaced, with Hughes stating confidently that he would rescue the trapped miner by 6 o’clock – the crowd applauded.

At 3.30pm, Hughes braved the waters without his diving suit and waded to Varischetti with food, where he sat with the miner, waiting for the water to lower more.

Newspapers reported an “animated scene” at the surface of the mine, with men waiting with the Union Jack and the Italian flag for when the men arrived.

While Varischetti was pale and weak from his ordeal, the crowds applauded all men involved in the tiresome rescue mission. Varischetti was lifted out of the cage by his hero, Hughes.

Varischetti, who was in a week and fragile state, opted out of a hospital visit, instead taken to the mine manager’s house and put to bed.

The Barrier Miner reported a warm welcome was waiting for the men upon arrival to the service:

“Varischetti had been held a prisoner for nine days. The rescue operations were attended with considerable danger, but were cheerfully carried out by the men, foremost amongst whom ranks the wellknown diver, Frank Hughes.

Diver Hughes, when he stepped off the skip, after the rescue of Varischetti, was mobbed, and kisses were showered on him by many women present. Inspector Crabbe, the mine manager (Mr. Rubischaum), Diver Curtis (who was in charge of the diving operations), Diver Hearne (who faithfully did the work with Diver Hughes), and their assistants, and those who had worked arduously below pumping air and cleaning out the place through which Varischetti was taken, were all heartily cheered.”

Varischetti remained at the mine manager’s home for several days to recover.

Hughes the ‘Hero’

The Sunday Times (Perth, WA), published the fllowing account from Hughes on Sunday March 24, 1907.

‘’Prior to going to work on the South Kalgurli Mine, where I am employed as a miner, I heard that a diver was required at the Westralia mine at Bonnievale, and with the desire of doing what I could to save a life I told the manager that I was prepared to offer my services. I went below at the South Kalgurli about 1.30 o’clock, but shortly afterwards was called and told that my offer had been accepted. I then left for Coolgardie by the half-past two train. On arrival I made a careful study of the plan of the Westralia mine submitted to me by Inspector Crabbe.

“As a result of my inspection I felt certain that I could get down the pass from No 9 level and reach the man. A special train bringing two other divers and gear arrived from Perth at about 4am. I reached the mine at 6.30 and we went below at 8.30am and I made the first descent at 10.30 from the No.9 to the No.10 level. I cleaned out the chute and waited for the arrival of an assistant, but there was no appearance of him. I went up again.

“I went down again shortly afterwards, but assistance did not come to light. Arrangements were then made for another diver (Hearne) to come down. Then somehow or other a misunderstanding took place while we were underwater. However, this being subsequently satisfactorily adjusted, I made my way along the drive to the rise at about 12 o’clock, leaving the other diver at the bottom of the rise so that he could attend to the lines.

“I followed the air pipe line through the level for a distance of about 250 feet, and on going up the rise found the airline and shook it four times. At the fourth shake I received an answering signal from Varischetti. Being thus assured that the man was alive and well, I made my way back to the No. 9 plat for a requisite spell. At about 4 o’clock I made another descent, taking a quantity of food in concentrated form and hermetically sealed, an accumulator, electric light, candles and matches.

“I may mention here that I heard the man sing out before he could possibly have seen me. I passed up the food and light, and in addition slate, which for protection had a wooden covering. Varischetti did not appear to understand the slate business at all, so I removed the covering and passed it to him again. When it came down I took it along to the plat but owing to the action of the water, the message he wrote was quite undecipherable. The slate bore the following message from the manager of the mine, Mr Rubischaum:- “Courage; rescue you in a few hours; food and light for you; keep above timber.”

While Varischetti was pale and weak from his ordeal, the crowds applauded all men involved in the tiresome rescue mission. Varischetti was lifted out of the cage by his hero, Hughes.

A Hero’s Medal

A year after the rescue, Frank Hughes was awarded The Albert Medal, second-class, for saving the life of Varischetti. The mines rescue initiative and selfless thinking made Hughes a hero

It was reported in the media that a fund was started for a testimonial to Divers Hughes and Hearne. The Chief Justice, Sir John Madden, who headed the list wired to the Government of West Australia:

“I earnestly applaud for Victoria the splendid humanity, heroism, and resource of all in the rescue of Varischetti, and, above all, their success.”

Mr. H. Mahon, M.H.R. has written to the Acting Premier (Sir John Forrest):

“You have doubtless followed the intrepid efforts made to rescue the Italian miner entombed at Bonnie Vale. The narrative has profoundly affected the whole community, and any step your Government may take on behalf of a national testimonial to recognise the splendid heroism of Divers Hughes and Hearne will be universally applauded. Such superb courage and daring would in other circumstances be rewarded by the Victoria Cross, but if that distinction be reserved for exploits on the battlefield your government may find some other means of commemorating this gallant feat, the inspiration of which was wholly humane and was wrought under the deadliest perils by two hitherto obscure heroes.” Hughes received a medal for his heroism and the Minister of Mines (Gregory) was decorated by the King of Italy.

Read more Mining Safety News or read some of our great Mining Safety History

Add Comment