Melissa Demarco is the Principal Lawyer with Demarco Law. In this article Melissa shares with us some insights in critical control management in the mining and resources industry.

CRITICAL CONTROL MANAGEMENT

A key focus of the mining and metals industry both internationally and in Australia, has been to identify and manage the acts (description of what a person should do), objects (a device that works without acts), or systems (combination of acts and objects) on mine sites required to either prevent, so far as reasonably practicable, serious incidents and/or high potential incidents from occurring or to minimise the consequences if incidents were to occur.

Critical control management (CCM) is defined as a process of managing the risk of material unwanted events (MUEs) which involves a systematic approach to ensure critical controls are in place and are effective. CCM is fundamental to risk management given that it focuses on identifying and managing the acts, objects or systems (i.e. controls) that are critical to preventing catastrophic or fatal events.

While conducting a post-incident investigation may, for example, assist to identify low performing or faulty controls, a continuous review and verification process will assist to prevent, as reasonably practicable, repeat serious incidents and/or high potential incidents from occurring, and assist to measure the effectiveness of controls introduced and/or introduce any additional controls that may improve the CCM process to prevent injury or illnesses so far as reasonably practicable.

The mining industry’s attention is focused on continuous investigative process which involves the review and consideration of the effectiveness of the controls in preventing disabling injuries and fatalities.

While the absence of serious accidents or incidents may be comforting in the short term, there is no guarantee that controls are working effectively and it may be only a matter of time before a serious incident occurs to find out. Without effective controls in place, the risk of an incident occurring will increase. This is evident from the multiple tyre fatalities discussed below.

WHAT DO THE STATISTICS TELL US?

The statistics on serious incidents and/or high potential incidents in Australia, specifically relating to the mining and metals industry (including coal mining, oil and gas extraction, metal ore mining, gravel and sand quarrying, and services to mining sectors) are significant, although lower in comparison to other high risk industries.

Safe Work Australia has recorded that between the years 2007 and 2012, approximately 36 workers in the mining and metals industry died in Australia from work-related injuries. The figures of work-related serious injuries or illnesses are extremely high. On average, approximately eight workers’ compensation claims are made per day in the mining and metals industry.

Various factors, including vehicle accidents, falls from height, being hit by falling and/or moving objects, physical and psychological stressors and, falls, trips and slips of a person, account for these fatalities and/or serious injuries.

EFFECTIVE & KNOWN CRITICAL CONTROLS

On February 8, 2016, the Senior Inspector of Mines in Queensland issued a statement following the anniversary of the two tyre-related fatalities in the Queensland mining industry.

- that work be done by both operators and manufacturers with an aim to ameliorate the particular dangers posed by high pressure tyres and multi component rims; and

- that continued development of Australian Standard 4457 be undertaken by the Mines Inspectorate and others, with special attention given to tyre handling, lock ring retention and rim maintenance.

The second incident referred to in the Senior Inspector’s statement occurred on February 16, 2015, at the Dawson open cut mine in the Bowen Basin, where the late Steve Cave had been working on a Cat 777 Position 1 assembly. The locking ring on a tyre he was fitting to a truck detached while the tyre was being inflated and suddenly exploded. Mr Cave was killed instantly and his colleague lost one of his arms.

The Senior Inspector’s statement noted several non-exhaustive, “effective and known ‘critical controls’ to mitigate the hazard and resultant risk” associated with working with tyres and rims to ensure that “the hard lessons learnt are not forgotten”. The statement reiterates the importance to ensure that critical controls are not only identified, but also effective in order to prevent recurrence of similar incidents.

However, between the coronial reports from Mr Marshall’s death in 2004 to Mr Cave’s death in 2015, there were several other fatalities and coronial inquests involving tyres not referred to in the Senior Inspector’s statement.

THE CRITICAL CONTROL MANAGEMENT PROCESS

The first incident occurred on February 9, 2004, at the Zinifex Century Zinc surface mine where the late Peter Marshall was removing a 3.5 tonne outer wheel from a large dump truck when suddenly the inner wheel released, throwing the outer wheel approximately 13 metres. As Mr Marshall was standing in the path of the wheel, he was driven across the tyre bay concrete apron and pinned underneath the tyre. Tragically, Mr Marshall sustained fatal injuries.

The findings of the inquest into Mr Marshall’s death delivered on 21 March, 2007, provided a number of recommendations highlighting the hazards of working with tyres and rims, particularly with higher tyre inflation pressures combined with considerable tyre volumes without effective controls in place. Those recommendations included:

- that an analysis of the safety culture at the mine be undertaken to inform management of how safe work practices can be internalised by staff of the mine;

- that the Mines Inspectorate investigate how meaningful supervision can be delivered to a heterogeneous workforce of autonomous skilled workers;

- that work be done by both operators and manufacturers with an aim to ameliorate the particular dangers posed by high pressure tyres and multi component rims; and

- that continued development of Australian Standard 4457 be undertaken by the Mines Inspectorate and others, with special attention given to tyre handling, lock ring retention and rim maintenance.

The second incident referred to in the Senior Inspector’s statement occurred on February 16, 2015, at the Dawson open cut mine in the Bowen Basin, where the late Steve Cave had been working on a Cat 777 Position 1 assembly. The locking ring on a tyre he was fitting to a truck detached while the tyre was being inflated and suddenly exploded. Mr Cave was killed instantly and his colleague lost one of his arms.

The Senior Inspector’s statement noted several non-exhaustive, “effective and known ‘critical controls’ to mitigate the hazard and resultant risk” associated with working with tyres and rims to ensure that “the hard lessons learnt are not forgotten”. The statement reiterates the importance to ensure that critical controls are not only identified, but also effective in order to prevent recurrence of similar incidents.

However, between the coronial reports from Mr Marshall’s death in 2004 to Mr Cave’s death in 2015, there were several other fatalities and coronial inquests involving tyres not referred to in the Senior Inspector’s statement.

On August 7, 2005, the late Mr Shane Davis, a truck driver for Korn Mining, was working a day shift at the Foxleigh open cut coal mine site when he noticed that one of the tyres on the vehicle he was driving was “doughy”. He went to the “Korn Workshop” at the mine site to attend to the tyre. A tyre fitter was employed at the workshop on a part-time basis, however it was the duty of the truck drivers to remove wheel assemblies with defective or damaged tyres from the vehicle, leave them to be attended to by the tyre fitter and replace the assembly with another.

Mr Davis was attending to this task when the drive wheel rim assembly he was handling gave way under pressure due to a wear crack in the rim. Mr Davis had not deflated the tyres on the wheel assembly. The tyre on the outer rim was forced from the assembly and it and parts of the rim struck Mr Davis, throwing him away from the vehicle. He suffered fatal injuries. On March 21, 2007, the findings of the inquest into Mr Davis’ death provided numerous recommendations. Significantly, those recommendations included:

- that the coal mine operators critically review the effectiveness and implementation of their mine safety and health management system;

- that the earthmoving committee of Standards Australia review the suitability of retaining rim sizes as a limiting factor in determining the applicability of Australian Standard 4457;

- that Standards Australia should review all associated tyre and rim standards; and

- that the Inspectorate liaise with other departments, industry, and professional bodies to ensure that the safety message relating to the hazard of uncontrolled release of stored energy from tyres, particularly when affixed to multi-piece rims and the need for training of those exposed to the hazard is disseminated across all industries and applications of the equipment.

Another incident occurred at the Foxleigh open cut coal mine on December 18, 2010, when the late Mr Wayne McDonald, a truck driver of LCR Group, had completed transporting nine loads of coal and called his base to inform that one of his trailers had sustained a flat tyre.

His supervisor directed him to drive to a location called “The Mailbox”, where the tyre could be changed. While Mr McDonald was changing the tyre, the tyre exploded. Mr McDonald suffered fatal injuries in his chest region from the forces of the blast. The mechanism of tyre burst was known as a Zipper Failure, named by its characteristic failure mode.

It is caused from fatigue of the steel belts supporting the pressure on the side-walls of the tyre which in turn is caused by running the tyre being overloaded, underinflated or flat for extended periods of time. One of the many recommendations provided by the coroner in the findings delivered on September 9, 2014, included that:

“an Australian Standard for up to 24-inch diameter truck tyres be investigated, created, and, if considered appropriate, implemented into law by regulation within a period of two years, and if no Australian Standard is created within two years then a Recognised Standard under Part 5 of the Coal Mining Safety Act 1999 be implemented within one year.”

It should be noted that the coronial inquests have all recommended, among other things, that Australian Standard 4457 be revised (in the Inquest of Mr Marshall) or alternatively, reviewed or created (in the Inquest of Mr Davis and Mr McDonald).

Recognised Standard 13, Tyre Wheel and Rim Management was was created and published by in November 2016.

ICMM GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE

In April 2015, the International Council of Mining and Metals (ICMM) published the “Health and safety critical control management: good practice guide”. This document is designed to provide guidance on the prevention of the most serious types of health and safety incidents or, MUEs through critical controls.

The CCM process is based on:

- having clarity on those controls that really matter (i.e. critical controls);

- defining the performance required of the critical controls (what the critical control has to do to prevent the event occurring);

- deciding what needs to be checked or verified to ensure the critical control is working as intended;

- assigning accountability for implementing the critical control; and

- reporting on the performance of the critical controls.

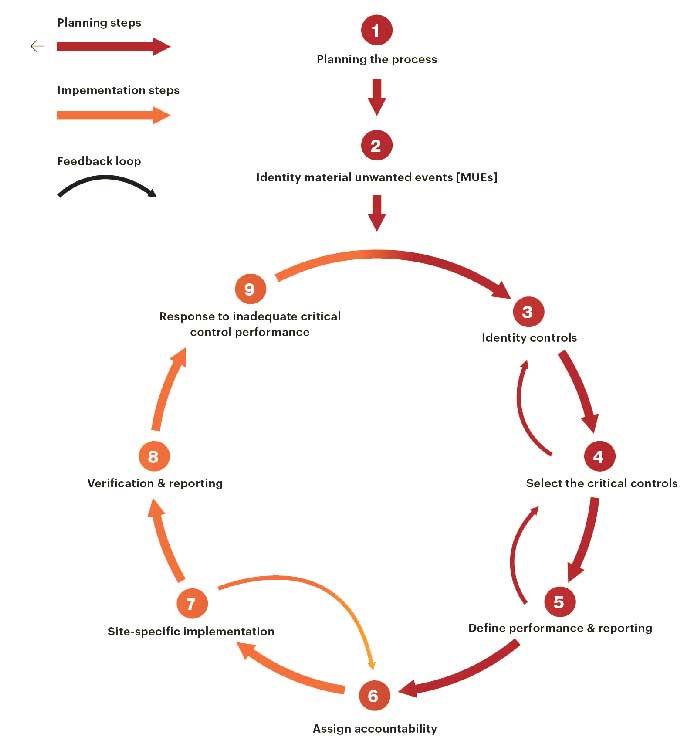

The CCM process has been specifically prepared for the mining and metals industry and sets out the following nine steps (as illustrated in the diagram below):

- Plan the process to understand the scope of the project, including what needs to be done and by whom.

- Identify MUEs that need to be managed.

- Identify controls for MUEs, both existing controls and possible new controls. Prepare a bow-tie diagram.

- Identify the critical controls for the MUEs.

- Define the critical controls’ objectives, performance requirements and how performance is verified in practice.

- Prepare a list of owners for each MUE, critical control and verification activity. A verification reporting plan is required to verify and report on the health of each control.

- Define MUE verification and reporting plans and an implementation strategy based on site-specific requirements.

- Implement verification activities and report on the process. Define and report on the status of each critical control.

- Respond to inadequate critical control performance.

EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION

In order to identify and manage critical controls to prevent a serious incident or injury from occurring, the effective implementation of controls is essential.

In summary, the successful implementation of a CCM involves:

- identifying the critical controls required;

- assessing the adequacy of critical controls;

- assigning accountability for the implementation of the critical controls; and

- verifying the effectiveness of the critical controls.

The ICMM has also published the Critical Control Management Implementation Guide, to be read parallel with the good practice guide.

The implementation guide provides generally, a summary of the CCM process, touching on the history of the discipline, its benefits, the challenges and how to prepare and plan to implement the CMM process. Further, the implementation guide also includes a step-by-step guide that uses health and safety case studies to demonstrate the approach, providing the actions needed to achieve the target outcomes within each step.

STEPS TO ENSURE THAT YOUR CONTROLS ARE EFFECTIVE

To ensure that the risk of a MUE is managed, controls must be working effectively. As mentioned above, the implementation of a continuous verification and reporting process will assist to understand and confirm whether controls are working effectively and if any modifications or improvements are required.

Steps that could be taken through the verification and reporting process to ensure that your controls are effective may include:

- provide a summary of verification activity results on a weekly/monthly basis;

- highlight any priority information (using a traffic light system);

- initiate immediate action for low performance or failures of critical controls;

- investigate and understand low performance or failures of critical controls; and

- identify any required improvements to and/or replacement of critical controls.

Importantly, it is critical to understand past incidents to ensure that hard lessons learnt are not forgotten and do not happen again.

MELISSA DEMARCO: PRINCIPAL LAWYER, DEMARCO LAW

Melissa Demarco is the Principal Lawyer at Demarco Law. Melissa has extensive experience in advising large employers in highly unionised industries and has a record of delivering practical solutions in complex disputes. She has extensive experience advising employers on a variety of issues involving Work Health and Safety, discrimination and harassment, redundancy, performance management and workers’ compensation matters. In addition, she assists employers with issues arising from employment contracts, awards and industrial instruments and workplace policies.

Read More Mining Safety News.

Add Comment