While open cut miners are familiar with working around sumps in mines, very few operators may consider the potential scenarios of drowning in a dozer.

The reality of an operator drowning in a dozer exists and is supported by a range of significant-high potential events across the industry spanning back several years.

While the probability of the event occurring is considered low, it’s clear that the range of significant-high potential events across the Australian mining industry is cause for reviewing the circumstances of those incidents.

Following the publication of our article on the ICAM investigation associated with the death of Dozer operator Allan Houston, and the subsequent potential for the inundation of the operator’s cab, we were provided with a significant body of evidence from a range of sources supporting the need for increased vigilance when operating near open cut mine sumps.

We have published that information as a means for industry operators to consider the risks when operating near or in sump areas.

Events occurring frequently

July 2018 – Peak Downs Mine

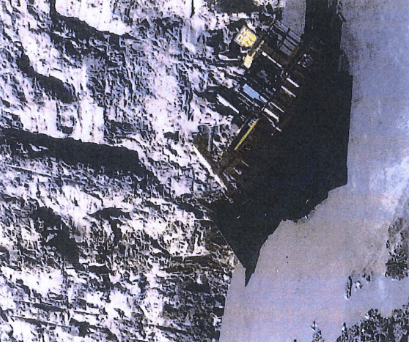

On the 8th July 2018 at the Peak Downs mine during the day shift, a task was allocated to an Excavator to commence a water management drainage task in the Peak Downs Mine pit along a high wall.

A deep and wide trench was dug for the intention of storing water against the high wall away from the dig face. During the process of digging the trench, a section was over dug beyond the pit floor.

With the completion of the trench, water was drained to the area resulting in a large pool of water forming in the trench, consequently covering the over dug area.

In the same day during the night shift, an Excavator and Dozer were tasked to commence top-loading coal within the pit.

As a part of the normal mining sequence, they top-loaded coal working north with water at the face and in the trench. The crew were unaware that an uncontrolled drop off in the trench had been created during excavation.

In line with normal practice, the Excavator and Dozer operators were mining the coal and managing the water at the face.

During the early morning (5:38 am) on 9 July, the dozer was working parallel to the high wall to clean the top of the parting to the excavator face, operating in a depth of water up to 700mm.

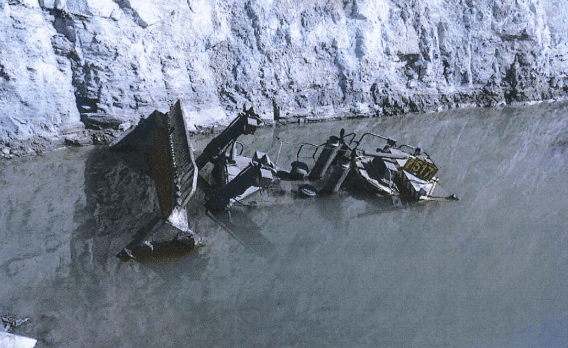

When reversing to exit the water area, the right-hand corner tip of the dozer caught something and the dozer pivoted towards the high wall resulting in the machine falling into the unknown void.

The dozer came to rest at an approximately 45-degree angle and water entered the cab. The operator was unable to exit the dozer and required assistance from nearby operators who swam to the dozer and broke the window glass, allowing the operator to exit the cab.

The findings included a lack of clear guidelines on water management, lack of adherence to trenching safe work instructions, no communication on an acceptable standard when operating in water. The investigation conducted by the company also identified a range of management and organisational issues associated with the event.

The high potential incident was reported to the Queensland Mines Inspectorate and processed on the 28th August 2018. There is no evidence that this serious event or the circumstances surrounding operating adjacent water bodies was communicated with other mines until a communique was issued in March 2019 following the death of Allan Houston in December 2018.

November 2013 – Bengalla NSW

On the 18th November 2013, a D11 slid into an unmarked test hole on a bench. The test hole had been dug two days earlier into a 5-metre thick overburden bench in an active mining area to determine the depth to coal. Heavy rain occurred on the previous shift and continued on the day of the incident, which filled the test hole. The dozer driver escaped the flooded cabin by levering the door handle with his foot.

at the shift prestart meeting the day-shift supervisor told workers about ponding of water at several dozer locations. The supervisor and the dozer driver were not aware of the existence of the test hole hidden below the water.

At 7.15 am the dozer driver approached the pooled water on the northern end of the bench in reverse. He stopped to test the water depth using the ripper blade. As the ripper blade was lowered the ground beneath the dozer slumped and the dozer slid backwards into the deep water and test hole. Water filled the cabin to head height. The driver was able to escape the cabin by levering the right-hand door handle with his foot.

The site conditions at the time of the incident were described by the dozer driver as wet and raining, with poor visibility, even though all the dozer windows had been cleaned. The dozer driver had 16 months’ experience operating dozers at the mine. The operator had received a site-based competency practical assessment on the operation of a dozer in July 2012. It was the dozer driver’s first shift at the mine after having the weekend off.

Two days before the incident an excavator was used to prepare the bench for a dozer to push the pre strip material off the bench and expose the coal. The excavator dug a drainage trench along the west side low wall of the bench to allow the flow of water from a higher level to drain. The excavator operator also dug a test hole at the north end of the bench in the end of the drainage trench to check the depth to coal.

There was a windrow on the southern side of the test hole. The excavator operator placed spoil material from the test hole on the east side between the test hole and the bench edge to complete the barrier around the open hole. While there was a windrow and spoil material around the test hole, there were no other physical means of identifying it or safeguards for the open hole such as guideposts, marking devices, GPS logging and recording, lighting tower or warning signs.

Contributing events As with most incidents there were events that contributed to the cause of the incident. Those significant events centre around the digging of the test hole and the four 12-hour shifts in the two days leading up to the incident.

The mine had an inspection program that included mining supervisors inspecting the area where mining operations were conducted. Over the five shifts there were three supervisors whose roles included the inspection and reporting of safety conditions in the mining area.

The following events set out the contributing factors: Shift 1 (Saturday 7am – 7pm) – the test hole was dug. Spoil material and windrows were put in place around the test hole. The supervisor was not told about the digging of the test hole. The supervisor did not identify that the hole was dug. Consequently, no action was taken to record or safeguard the exposed hole. Shift 2 (Saturday 7pm – 7am), the test hole and windrow remained in place. The supervisor did not identify the test hole and therefore was not aware of the hazard or risks posed. Shift 3 (Sunday 7am -7pm) – the test hole and windrow remained in place. The supervisor did not identify the test hole and hazard. Shift 4 (Sunday 7pm -7am), rain started with several heavy falls and continued throughout the day.

Water filled the test hole, the drainage trench and ponded on the bench. The test hole windrow was removed to help the water drain from the trench. The night-shift dozer driver did not inspect behind the windrow and did not know about the test hole.

The night-shift supervisor and oncoming day-shift supervisor conducted a handover inspection of the area together. Neither supervisor had knowledge of the test hole or suspected that there may have been deep water in the trench.

The incident had serious consequences and was investigated by the NSW Regulator and promulgated to industry.

29 June 2017 – Peak Downs

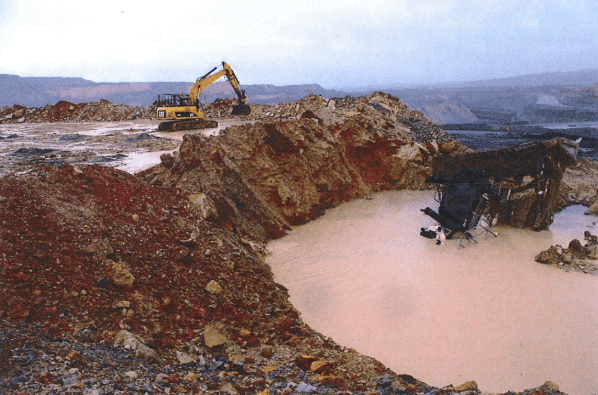

While pushing out the mud in the pit, a dozer reversed into a sump that the operator had excavated earlier that shift. The displacement triggered the emergency stop which prevented the operator from tramming back out.

The investigation found that drowning risks are not confined to traditional water body activities, they also apply to in-pit mining activities specifically those that are related to trenching and sumps (including what is considered a ‘shallow’ water body), and risk assessment and risk management should be applied to these scenarios.

The report found that it is necessary to consider all possible scenarios on sites for hazards and utilise learnings from outside our business within the industry.

The report also highlighted the need for comprehensive handovers to adequately communicate safety hazards and risks are of critical importance, with the handover understood and a plan is in place to manage any high-risk work.

It is unclear if this information was communicated to mines inspectors.

May 2011 – Mount Thorley Warkworth

A dozer operator was normally a member of the Pit Services Crew ‘C’ and reported to a mining supervisor.

The operator was a competent mineworker who usually operated a dozer but could also operate many of the mine’s associated equipment, such as trucks, graders and front end loaders.

On Sunday 15 May 2011, the dozer operator arrived at the mine and was placed with the Coal and Partings production team that was to work in the Moorelands Pit.

He reported to the supervisor and support open cut examiner for coal and partings, and was sent to operate the dozer.

The dozer operator had worked at in the Moorelands Pit previously. He had started work with the coal and partings team at the coal bench on Friday 13 May 2011, ripping coal with his dozer ahead of a front end loader that was loading the haul trucks.

On the day of the incident, the employee exposed to risk was operating a CAT D11T dozer and was told by his mining supervisor to move the pooled water from the southern end of the coal bench to the pump at the northern end.

The purpose of moving the water was to gain access to a strip of coal that was covered by the water. At 7am the mining supervisor and the dozer operator went to the southern end of the water on the coal bench and got out of their vehicles to meet.

The mining supervisor inspected the area from the eastern side of the water expanse and gave the dozer operator his work instructions. No attempt was made to determine the depth of the water. As the pump at the northern end was marked with a sump warning sign, both men assumed this was the only sump on the bench.

The dozer operator was instructed to cut a drain in the coal bench, in the eastern side of the expanse of water, to get the water to move more freely towards the pump at the northern end. The drain was to be cut right up to near the pump. To do that the dozer operator had to travel through, and work in, the water on the bench.

He had been informed by his mining supervisor that the area covered by the water hadn’t been mined so the floor would be hard. The dozer operator started work at the southern end and used the edge of the dozer blade to create the small drain to the north and towards the marked sump.

After tipping a small drain, he reversed his dozer back through the expanse of water, and began pushing water to the north with the blade of the dozer. He saw that water was escaping out the southern end through a gap between the windrow of partings material (interburden) near the highwall. He decided to reverse over the low section between the partings and the highwall to repair the windrow by pushing more material up into the area to prevent the water escaping.

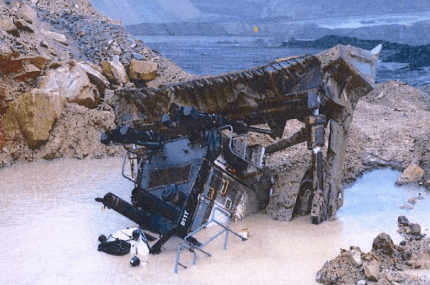

At 7.30am the dozer operator reversed over the pile of partings and felt the dozer sliding into deeper water. He attempted to drive the dozer out of the water but could not get enough traction and began to sink. The dozer sank into the deep water sump.

The dozer operator later told investigators he was unable to open either of the cabin doors due to the water pressure. He said that although he initially panicked, his training in emergency response allowed him to calm down and wait for the water to fill the cabin.

There was nothing in the cabin to enable the dozer operator to smash through the windows. As the water rose inside the cabin he tried to open the right hand door by banging on the door lever to escape. After several attempts to open the door he waited until the water almost completely filled the cabin and the pressure equalised. He was able to open the door and escape.

The man swam about 10 m to the water’s edge and bank of the windrow where the people who were first at the scene were gathering.

The Regulator investigated the incident and identified a range of Controls for the risk of sumps. The following is a summary of those controls.

Permit to dig Sumps should not be dug without the approval of the mining supervisor for the inspection area. A written record is kept of the request and authorisation to dig. The record includes an accurate location of the sump. Locate by a survey.

Windrows and signs: A physical barrier, such as a windrow, is constructed around the sump. The windrow indicates an edge and present danger. Cautionary or danger warning signs are to be placed at all directions of access to the sump. No sign is to be removed until the sump no longer presents a risk to people in the area.

When against the highwall identify the sump by additional means such paint marks on the highwall, danger markings or poles on the top of the highwall, or marker buoys or signs hung over the highwall edge.

Other physical methods of identifying the risk should be employed as well as the windrow and signs, such as traffic cones or crossed-sticks. Record of location and re-locating sumps When a sump has been dug the location must be noted. The sump should be surveyed and the co-ordinates recorded and kept.

The sump location must be recorded on the open cut examiner inspection sheets to inform supervisors of the risk in the inspection area. As open cuts and work areas such as the coal bench in the Moorelands Pit are susceptible to water inrush from rain and water issuing from the coal seam and strata the physical barriers, signs may become covered, as was the case with the incident sump.

When such change to the physical working environment has occurred, the sumps should be relocated and identification re-established if none of the previous markers remain.

Coal operations, both surface and underground, are now highly mechanised and technical workplaces.

There are many modern systems that are readily available to assist in locating known sumps. GPS technology can be used in surveying the sump, and to assist in locating the sump by way of hand-held and mobile GPS units. The co-ordinates of known sumps can be pre-loaded into a hand held units.

Mobile plant such as dozers may have GPS equipment installed. The sump co-ordinates can be pre-loaded into the dozer unit and an alarm set that will give an audible and visible warning when the dozer comes within a set distance of the sump.

Mobile plant such as dozers may have GPS equipment installed. The sump co-ordinates can be pre-loaded into the dozer unit and an alarm set that will give an audible and visible warning when the dozer comes within a set distance of the sump.

NSW Mines Inspectorate

Safe work procedures The above controls require the development of, and implementation of, written instructions and procedures to ensure that all controls are placed correctly and in a timely manner. Monitoring and auditing

The standards for risk management of sumps will not be maintained unless monitored and audited. Such monitoring and auditing procedures should be in place to verify the performance of the safeguards to prevent machinery from entering deep water sumps.

Evidence base growing

The available formal evidence together with a significant range of anecdotal evidence provided by operators has highlighted the need for effective engineering and administrative controls when working with machinery around water. Understanding that engineering controls have existed for several years makes the spate of recent events even more concerning.

Read more Mining Safety News

Add Comment