Sophie Blackshaw takes a look back at Tasmania’s mining past and examines the lead-up and aftermath of the Briseis Tin Mine Dam Disaster of 1929 where the burst of a dam wall took with it a part of the community.

Geographically more like New Zealand, with its mountainous terrain and snowcapped peaks, Tasmania is a state not often considered when the topic of Australian natural disasters arises. Yet, as isolated and different from the mainland as it may be, the Apple Isle has dealt with some of the cruellest disasters in the history of the country’s European settlement. Fires, heat waves and earthquakes – albeit seismically small ones – have consistently been at the root of ruin in the state, impacting the mining industry on multiple occasions.

Situated about 228km north of Hobart and 94km northeast of Launceston, is Derby, a modest but formerly very prosperous town that experienced one of these destructive and fatal disasters for itself, and timed right on the eve of the Great Depression to worsen the matter.

Situated about 228km north of Hobart and 94km northeast of Launceston, is Derby, a modest but formerly very prosperous town that experienced one of these destructive and fatal disasters for itself, and timed right on the eve of the Great Depression to worsen the matter.

A well established little town with its own school, a boarding house, doctors’ residence and hospital, two butchers, two bakeries, three hotels, and a cordial factory among other businesses, much of Derby’s success could be attributed to the state’s booming tin mine industry. Specifically, it could be linked to the Briseis tin mine, located a very short five kilometres to the northeast of town.

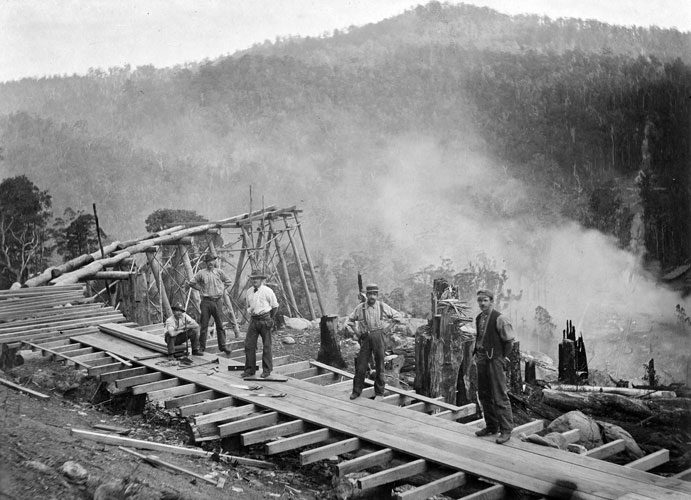

While production at the hydraulic tin mine in its early years was intermittent and, according to the Briseis Central Tin Mine Company, “very inefficient”, by 1929 the operation was incredibly lucrative.

Unfortunately, the mine and its economic glory were fated to an abrupt ending on Thursday April 4, 1929, when days of torrential rains began to take their toll on the northeast corner of Tasmania.

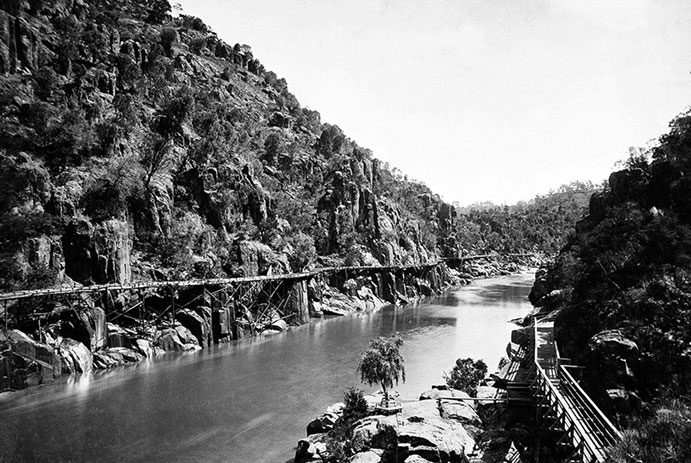

Situated between a main road and Ringarooma River to the east, Briseis was one of the richest and most profitable tin mines in the world, employing hundreds of men and exporting millions of tonnes of tin to countries all around the world.

Unfortunately, the mine and its economic glory were fated to an abrupt ending on Thursday, April 4, 1929, when days of torrential rain began to take their toll on the northeast corner of Tasmania. Derby was quickly inundated with a recorded 475mm dropped on the town over the day, but it was the additional 125mm that fell over an hour-and-a-half on the catchment above the community’s chief source of water – the Cascade Dam – that was the match to the gasoline.

Unfortunately, the mine and its economic glory were fated to an abrupt ending on Thursday, April 4, 1929, when days of torrential rain began to take their toll on the northeast corner of Tasmania. Derby was quickly inundated with a recorded 475mm dropped on the town over the day, but it was the additional 125mm that fell over an hour-and-a-half on the catchment above the community’s chief source of water – the Cascade Dam – that was the match to the gasoline.

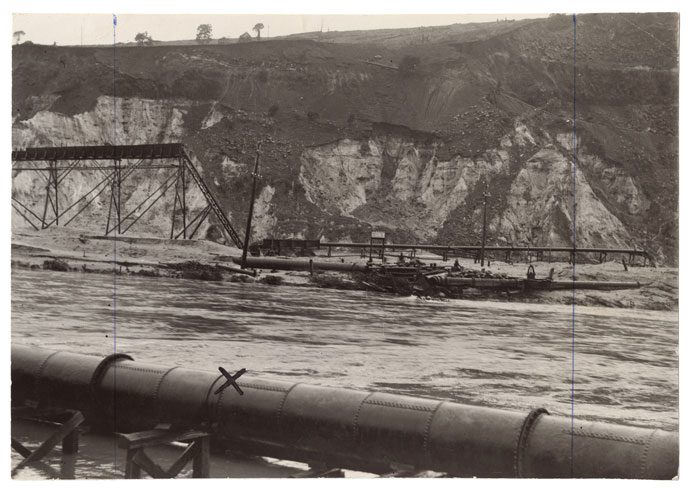

At 4 pm on the day, the Cascade Dam wall burst and released more water than was needed to rival Niagara Falls. Witnesses reported that in the hours that led to the wall’s demise, water had been tumbling violently over the top and into the Cascade River. Now the river had become, wrote Australian Book of Disasters author Larry Writer, “a 32-metre wall of water containing trees and boulders – including one 10-tonne specimen”.

At 4 pm on the day, the Cascade Dam wall burst and released more water than was needed to rival Niagara Falls. Witnesses reported that in the hours that led to the wall’s demise, water had been tumbling violently over the top and into the Cascade River. Now the river had become, wrote Australian Book of Disasters author Larry Writer, “a 32-metre wall of water containing trees and boulders – including one 10-tonne specimen”.

For the people living in Derby and the surrounding towns, it was a catastrophic event at once unprecedented and previously unimaginable. The uncontrolled muddy water actually caused the river to reverse its course and flow uphill for an incredible ten kilometres. With its considerable volume of debris, it doomed anything and everything unlucky enough to have been grown or built in its path, including peoples’ homes, the railway station, and every single bridge crossing the river, including Cataract Gorge approximately 94km away.

READ RELATED CONTENT

Also situated, regrettably, along the river’s condemned route was the Briseis tin mine. Sadly, despite the rains, a number of men were still working in the mine, as unaware of the oncoming torrent as any other person. Larry writes that the mine’s assistant manager, William Beamish, who somehow had a moment’s notice more than the others, attempted to warn them, “Instead of running for higher ground … he turned and returned to the face, crying for his workmates to run for their lives.” Beamish’s courage cost him his life when he was swept away by a wave, dragged under and failed to resurface.

In town, witnesses noted similar acts of bravery when residents risked their lives and their cars in efforts to pluck out those caught up in the filthy water.

“Reported one witness: ‘The motor drivers spared neither themselves nor their cars in their endeavours … the air was full of the raucous notes of motor horns. It was truly a wonderful sight, and the manner in which the motorists dashed into the water with a total disregard for risk was a wonderful tribute to [them] …There were no social distinctions and everyone worked with a will.’” (Larry Writer)

In an article published after the flood, when Launceston and the rest of the country found out about the incident, a reporter offered a description of the palpable courage seen among both townspeople and Briseis tin miners.

“The heroism of the assistant manager of the Briseis mine, Mr W.A Beamish, while trying to warn the miners to reach safety, the valour of senior constable W. Taylor who, single-handed in a small boat, braved the rushing waters and brought many men to dry land, and many other instances of supreme heroism serve to make what will go down in history at the ‘Briseis Disaster’ another bright page in the book of Tasmania’s deeds of self-sacrifice and heroism associated with the mining industry.”

The constable who rescued the men did so one at a time, since the boat he used was said to be either the size of a kayak, or an actual kayak. Regardless, it fit only two men concurrently. For his efforts, he was later awarded the Royal Humane Society Medical and the King George Medal.

In all, fourteen people, including one woman, were swallowed by the torrent. Most of them were miners, but five of them were members of the Whiting family, whose home was obliterated by the raging wave while they were eating dinner. The one woman was presumed by Tasmanian newspapers to have been Alice Whiting – although her body, examined by “duly qualified practitioner” Dr George Arthur Jones, was beyond identification.

As if knowing a relative or partner had been killed in a natural disaster was not traumatic enough, many witnesses reported seeing people being swept away, including the wives of miners who drowned. One local, W. Kerrison, said he and his wife “saw Richardson, Broadley, Bracey and Eadie coming from the timber stack towards the stables … When I saw the water I called out, ‘Run for your life, the dam has gone.’”

Larry confirmed that it was the wives of Broadley and Richardson whose husbands’ lives were taken before them.

Kerrison continued: “[My wife and I] ran up the hill about 20 yards and as I turned I saw the water in a huge, muddy foaming wave … It took the stables in its course, together with several of the men and eight draught horses.”

“… I never want to see such an awful sight again. I saw the water rush across the flats to where the men were working on the lower face [of the tine mine]. It was impossible to warn the men. It all happened so quickly.”

Another witness, George Inverarity, whose house near the mine was demolished by the water, said his wife heard “’heart-rending screams’”.

In more ways than one, the flood’s aftermath was as difficult to accept as the destruction and death reaped by the furious surge itself. The force of the water had carried the bodies of the drowned many kilometres from where they were taken, concealing them with mud and wreckage. While different sources give slightly differing dates, The Advocate newspaper at the time reported that search parties were organised when the water subsided and on April 6, Raymond Whiting’s body was discovered beneath the Inverarity’s home.

Two days later, Stephen Daly and Patrick Whiting’s bodies were found. On April 15, Hector Michael McCormack’s remains were recovered more than six kilometres from the mine, downstream in the Ringarooma River. Samuel Bradley Cave was also found nearby.

On the matter, Larry said: “No reminder was more heart-rending than the discovery of the final two unaccounted-for bodies of those killed in the Briseis mine … McCormack left behind a widow and two children.”

What must have served as an unwanted distraction were the inevitable health warnings issued by Tasmania’s Secretary for Public Health E.J Tudor not long after the flood. Mr Tudor said that the South Esk River, a main water supply for five large towns about 100km southwest of Derby, had been polluted by the carcasses of dead farm animals, and that local authorities would be instructing people to boil all their water to reduce the risk of a disease outbreak.

When the clean-up began and the affected towns of northeast Tasmania were again able to make contact with the rest of the state – they had been cut off by the rain for days – money, food, clothing, and other donations began making their way to those affected.

For those who worked at the Briseis tin mine and survived the disaster, they could be grateful to still have their lives, but their source of income had been washed away with the boulders, the trees, peoples’ possessions, their homes and their loved ones.

According to a statement in a deputation made in 1936 by Tasmanian politicians and businessmen, Briseis Central Tin Mining Company invested £90000 into the mine›s rehabilitation in the months after the tragedy. The work included rebuilding the mines power station and offices which were destroyed. Only four months later, the company’s fiscal investment proved to be in vain when another 508mm of rain fell and refilled the mine. It would be another ten years before the mine would be rebuilt and return to full production – just in time for the resource demands of another massive world event: World War II.

Before reopening, however, a Coroners Inquest was conducted to examine if those killed in the Briseis Dam Disaster were preventable deaths, or attributable in any way to an individual or body. The conclusion the jury came back with, after a 35-minute retirement, was that the disaster was due to the “effect of cloudburst” and “no blame was attachable to anyone”.

The significantly damaged Cascade Dam wall was rebuilt in the 1930s, and today remains Derby’s main source of water. A bronze statue, moulded into the shape of a grieving woman and child, commemorates the lives of husbands, fathers and relatives lost in the disaster. It stands outside the Tin Dragon Interpretation Centre and Café (or the Tin Centre), part of the Trail of the Tin Dragon tour route in northeast Tasmania.

RESOURCES

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/67822081 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-title46

Writer, L. 2011. Australian Book of Disasters. Murdoch Books Australia, Australia. Pages 51-59

Read more Mining Safety News

Add Comment