Mining ergonomics expert, Robin Burgess-Limerick, discusses how to prevent slips, trips and falls during mining equipment access and egress.

Access to, and egress from, mining equipment is an important, and frequently overlooked, aspect of equipment design. Poor access can result in musculoskeletal injuries due to overexertion and awkward postures, as well as increasing the probability of slips and falls during access or egress.

Injury records clearly demonstrate this is a common injury mechanism at both surface and underground mines (Burgess-Limerick & Steiner, 2006; 2007). Santos et al (2010) reported that about 25% of injuries associated with haul trucks in the USA over a five year period involved slip, trip fall; and that this was most commonly associated with egress from equipment. Similar results were obtained from an analysis of surface coal mining equipment injuries in New South Wales (Cooke et al., 2012). As well as injuries of varying severity, fatalities have resulted from falls associated with equipment access systems. For example, in 2009 a driver fell while cleaning the window of her haul truck at a Western Australian mine, and subsequently died.

For these reasons, the issue was an early priority of the Earth Moving Equipment Safety Round Table (emesrt.org) and is addressed by an “Access & Working at Heights” design philosophy. The EMESRT design philosophy aims to ensure that equipment is designed to consider:

- Stairways, walkways, access and work platforms, railings, steps/grab handle combinations and boarding facilities including an alternate path for disembarking in case of emergency.

- Ergonomically considerate access systems that allow three points of contact to be maintained and minimise the risk of sprain or strain.

- Access systems and work platforms that are well lit, located and designed to minimise their impact on operator vision, and clear of slip and trip hazards.

- Openings designed to account for body size variability, escape apparatus and personal protective equipment (PPE).

- A priority outcome would also be ground entry to access on driver’s side, with the opportunity to locate isolation and other service points (hydraulic, air) near the driver’s side operator access.

- Location of service points, inspection points and ancillary equipment that eliminates the need to work at heights, during routine maintenance or repair.

- Provision of work platforms with suitable controls to eliminate the need to work at height and prevent the risk of tools and other objects falling onto people below.

- Where it is impractical to provide equipment mounted work platforms, the design of appropriate roll up access and work platforms or other means for workshops.

“…25% of injuries associated with haul trucks… involved slip, trip fall; and that this was most commonly associated with egress from equipment.”

Similarly, the RISKGATE project (riskgate.org) identified slip, trips and falls as one of the 18 topics on which the industry risk management database would focus. RISKGATE employs Bow Tie Analysis as a framework for capturing knowledge. At the centre of each bow tie is an initiating event. The range of potential causes is listed for each initiating event, as are the potential consequences. For each cause, the potential control measures are identified (preventive controls), and measures which can be taken to reduce the severity of the consequences of each initiating event are identified (mitigating controls).

“Loss of balance during access or egress to/ from mobile plant” was identified as one of three initiating events addressed within this topic. Mobile equipment was considered to include self-propelled machines or machines that are transportable around the mine including: haul trucks, water tankers, drill rigs, prill trucks, industrial lift trucks (e.g. forklifts), mobile cranes, earthmoving equipment (graders, dozers, shovels, excavators, scrapers, wheel loaders etc.), draglines, lighting towers, continuous miners, elevated work platforms (EWPs), stacker reclaimers, shearers, LHDs and shuttle cars etc.

Causal factors for slips, trips and falls identified within riskgate relate to equipment design (e.g. access system, handrails, operability and maintainability of equipment requiring access), carrying items or tools, distraction, foreseeable misuse (including human behaviour/concentration lapses/mistakes), fitness for work (including fatigue, impairment/ drug usage, etc.), less than adequate footwear, visibility or lighting, environment (weather and climate, contaminants, etc.), and provision for emergency escape.

Controls for the management of slips/trips/ falls during access/egress to mobile plant identified within Riskgate include:

- Elimination or reducing exposure (e.g. platforms for maintenance, remote operation, maintenance and inspections performed from ground level).

- Design of equipment access or environment in which equipment is located for access.

- Optimising environmental conditions (e.g. lighting, drainage, roadway maintenance).

EQUIPMENT ACCESS DESIGN

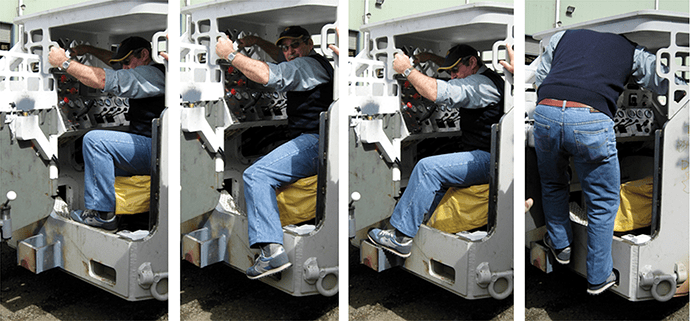

Access /egress design requires consideration of the step height and reach distances capabilities of the smallest potential operator. Standards such as AS3868 and AS1657 provide guidance for access /egress, and specify for example the maximum step height of 400mm. While the provision of ladders for access is common, the risk of falling is relatively high, and stairs are preferable. For example, while the access system illustrated in Figure 1 is typical, an innovative access system incorporating stairs rather than ladder access has been provided in the underground dozer illustrated in Figure 2. Similarly, cut-out footholds are common, and while satisfactory for access, are difficult to use during egress, as illustrated in Figure 3.

READ RELATED CONTENT

Access systems provided on older haul trucks such as that illustrated in Figure 4, and other large surface mining equipment are now considered unsatisfactory, and this created a need for after-market access solutions provided by other vendors (eg., www.hedweld.com.au) to be fitted. More recently, and, in part at least, encouraged by the activities of EMESRT, the original equipment manufacturers of haul trucks have provided much-improved access systems utilising stairways rather than ladders.

Access and egress to equipment is a specific example of a more general design goal of reducing the possibility of slips and falls during operation, and ensuring safe access and working conditions during maintenance activities. The design of working and access platforms on equipment requires careful consideration, regardless of the height of the platform (eg., Figure 5), as does the design of access systems for maintenance (eg., Figure 6).

STATISTICS ON SLIPS, TRIPS & FALLS FROM SAFE WORK AUSTRALIA

According to the Safe Work Australia report, one in five serious work claims in Australia involves an injury to the back.

NATURE OF INJURY OR DISEASE

The most common work-related injuries that were compensated were sprains and strains (42.4% of all serious claims). In 2011–12, injury or poisoning accounted for 72% of serious workers’ compensation claims with disease claims accounting for the balance. However, the number of disease claims is likely to be an underestimate due to the difficulties associated with linking disease to workplace exposure(s).

HOW THE INJURY OR DISEASE OCCURRED

Body stressing, Falls, trips & slips of a person and Being hit by a moving object were the mechanisms of work-related injury or disease responsible for 75% of serious workers’ compensation claims in 2011–12.

These mechanisms, together with, were identified as priority mechanisms in the National OHS Strategy 2002–2012. There has been little change in the proportion of claims due to these mechanisms since the National OHS Strategy began.

SERIOUS CLAIMS: PERCENTAGE BY MECHANISM OF INJURY/DISEASE, 2011-12P

INJURY & MUSCULOSKELETAL CLAIMS

As a step towards achieving its national vision of Australian workplaces free from death, injury and disease, the National OHS Strategy set the following targets:

TARGET: 40% reduction in the incidence of work-related injury by 30 June 2012.

RESULT: There was a 28% decrease in the injury incidence rate up to 2011–12.

PROFILE

PROFESSOR ROBIN

BURGESS-LIMERICK

Professor Burgess-Limerick is an experienced human factors and ergonomics researcher and consultant across a range of industries including mining. He is currently undertaking projects in the areas of equipment design to reduce injury risks, manual task risk management, and whole body vibration measurement and management. Robin has authored more than 100 papers, chapters and books, and is a past-president and Fellow of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society of Australia.

Robin Burgess-Limerick PhD CPE Professor of Human Factors Minerals Industry Safety and Health Centre The University of Queensland, 4072 r.burgesslimerick@uq.edu.au

REFERENCES

Brenda R. Santos, William L. Porter, Alan G. Mayton (2010) An Analysis of Injuries to Haul Truck Operators in the U.S. Mining Industry. PROCEEDINGS of the HUMAN FACTORS and ERGONOMICS SOCIETY 54th ANNUAL MEETING – 2010 1870-1874.

Burgess-Limerick, R. & Steiner, L. (2006) Injuries Associated with Continuous Miners, Shuttle Cars, Load-Haul-Dump, and Personnel Transport in New South Wales Underground Coal Mines. Mining Technology (TIMM A) 115, 160-168.

Burgess-Limerick, R. & Steiner, L. (2007) Opportunities for preventing equipment related injuries in underground coal mines in the USA. Mining Engineering. October, 20-32.

Cooke, T., Horberry, T. & Burgess-Limerick, R. (2012). Revisiting injury narratives to pinpoint human factors issues associated with surface mobile mining equipment. In Proceedings of the Occupational Safety in Transport Conference. Gold Coast, Sep 20-21. CARRS-Q, Queensland University of Technology. ISBN – 978-1-921897-53-5.

Lynas, D., Burgess-Limerick, R & Kirsch, P. (2014). Riskgate analysis of Slips, Trips and Falls in surface and underground coal mines. Journal of Safety and Health Research and Practice, 6, 2-7.

Moore, S.M., Porter, W.L., & Dempsey, P.G. (2009). Fall from equipment injuries in U.S. mining: Identification of specific research areas for future investigation. Journal of Safety Research, 40, 455-460.

Add Comment